The Last Whaler

Painting shows whaleboat harpooning its prey. Credit:New Bedford Whaling Museum

It’s believed the Industry, built in 1815, was seeking new grounds for harpooning sperm whales, the favorite species of the whaling bunch in 1836, when it ran into a fierce storm and sank in 6,000 feet of water. Fortunately, another whaling ship was nearby and rescued all 15 men and returned them to New England. Dr. James Delgado, marine historian and archaeologist, said, “They were lucky. You can cruise the Gulf for many miles without seeing another vessel.” His age old whaler’s cue, “Thar she blows,” was fitting for letting the crew know he had spotted something interesting. In this case it was the profile of a wooden ship ravaged over the years by toredo worms.

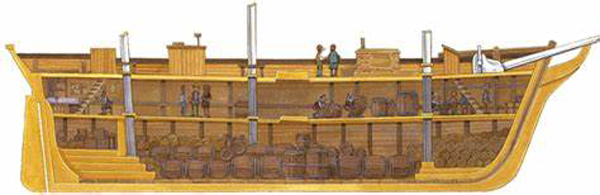

A whaling factory ship included sections for eating, sleeping and butchering the whales. Credit: SEARCH, INC. and NOAA

Delgado heads SEARCH Inc., a survey team of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that seeks historical shipwrecks when it’s not assigned to other cultural heritage projects worldwide. His team of maritime sleuths, aboard the research vessel Okeanos Explorer, scanned the ocean floor 70 miles offshore from Pascagoula, Mississippi, in February, 2022. Strong lights on their remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) lit up the bottom revealing an outline of a 65-foot square-rigged brig. Old news clippings from the Nantucket Inquirer and Mirror featured the loss of the Industry in a fierce storm and the rescue of its crew by the Elizabeth, another whaler in the Gulf. The rescued men were returned to their home port in Westport, Massachusetts, where blacks were not enslaved. In addition to the wreck’s profile, Delgado’s photos showed anchors and a metal and brick tryworks which was a small furnace with iron kettles used to extract oil from the blubber of the whales. Rum and whisky bottles from the era were spotted along with some of the Industry’s hardware, but the ship’s nameplate wasn’t found. Nothing was salvaged at this time.

Whaling ships at dock, New Bedford, (circa 1800). Barrels of oil are on wharf. Credit: National Archives

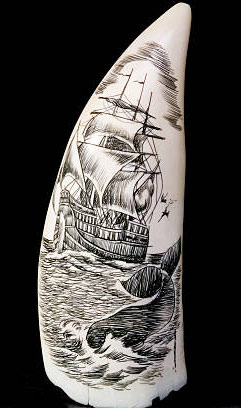

Lazy days were filled with scrimshaw art on whalebone or whales’ teeth. Credit: New Bedford Whaling Museum

Ships were usually brigs, barks and schooners, double-hulled for protection against ice and attacking whales. In Melville’s book, the story revolves around the obsessive quest of Capt. Ahab who sought revenge on a great white sperm whale that bit off his leg at the knee on a previous voyage. The Industry was small at 65 feet. Later, larger vessels appeared on the scene as factory ships processing the blubber (oil), whalebone (baleen) and spermaceti (special oil taken from the head of a sperm whale) used in manufacturing candles and cosmetics. Sperm, Right and Bowhead whales were special. As much as three tons of oil could be extracted from one 50-foot, 100-ton sperm whale. The largest one reported was a blue whale in the Antarctic estimated to be at least 190 tons. The meat was eaten mostly by the Japanese, Norwegians and Icelanders. Some people still eat it after arranged killings are permitted on over-stocked pods.

Artifacts on the sea floor include a tryworks furnace used to heat blubber. Credit: SEARCH, Inc.and NOAA

Although Rockefeller did his part, it was the International Whaling Commission (IWC) that set quotas and finally, by 1982, banned commercial whaling. Eight species are considered endangered. Neither the IWC nor any of the other organizations that might have favored continuation of commercial whaling could come close to matching its third reason for collapse coined by Greenpeace, USA: “Elimination of the cruel, unnecessary and inhumane slaughter and butchering of one of the world’s greatest sea creatures.”

Note: Whaling enthusiasts must visit The New Bedford Whaling Museum, one of the finest marine museums in the country. New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Author: Ellsworth Boyd

Ellsworth Boyd, Professor Emeritus, College of Education, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, pursues an avocation of diving and writing. He has published articles and photo’s in every major dive magazine in the US., Canada, and half a dozen foreign countries. An authority on shipwrecks, Ellsworth has received thousands of letters and e-mails from divers throughout the world who responded to his Wreck Facts column in Sport Diver Magazine. When he’s not writing, or diving, Ellsworth appears as a featured speaker at maritime symposiums in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, New York and Philadelphia. “Romance & Mystery: Sunken Treasures of the Lost Galleons,” is one of his most popular talks. A pioneer in the sport, Ellsworth was inducted into the International Legends of Diving in 2013.

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Thanks for another enjoyable article Mr Boyd. Personally I’m glad that the whaling industry’s heyday is mostly over. I do hope that, with exception of respecting indigenous whaling peoples rights, that mechanized whale hunting will cease.

Rick

Thanks Rick. I’m glad you liked my article. I agree with you. Indigenous people are the only legitimate fishermen who should be given permission to take them. As more people are reading and learning about the whaling industry, they are backing Save the Whales and other Conservation of the Seas groups. Aren’t the kill figures in those early days astounding?! There should have been more conservation groups organized back then. The only celebrity I know of who steps up and speaks about saving the whales and the seas is Ted Danson. I wish there were others.