Siege of Charleston

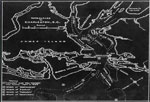

Siege of Charleston expedition to find Hunley and survey for other Civil Warships. June, 1981.

We came back with a more extensive search program in ’81, concentrating on covering a sixteen square mile grid between the remains of the Housatonic and Breech Inlet. During this project, Alan Albright, chief state archaeologist with the U. of South Carolina, generously loaned an outboard boat, equipment and the services of two damned fine men, Ralph Wilbanks and Rodney Warren, who proved indispensable.

The research had gone on nonstop during the year. I was determined to locate as many Civil War shipwrecks as possible. The plan was to conduct two ongoing projects; the search for the Hunley and a survey for nearly ten other ships that sank in Charleston during the Civil War.

While the small boat mowed the lawn over the Hunley grid, our large boat, skippered by Harold Stauber, carried the divers and dredging equipment and used its free time looking for other sites. (The list of ships and their locations, if found, are included at the end of this section along with the paper presented to the 13th Conference on Underwater Archaeology by Bob Browning and Wilson West, who worked tirelessly during the project.)

Nearly everybody associated with NUMA showed up for this search, including our President, Admiral Bill Thompson. Schob, Gronquist, Shea, the Goodwins, Dirk and Barbara, the mini-ranger people from Motorola, Bill Hatcher and Dave Graham and Bill O’Donnell, all returned. Erick Schonstedt came and set up his fine gradiometer. Everyone stayed at a house we rented on Sullivan’s Island.

After studying our data from the previous year, we came up with a few new tactics. For one, we put the mini-ranger transponder on the boat and left the operators on shore. They sat in a comfortable van on the beach and simply directed the helmsman of the University’s boat by radio. This proved very efficient and a hell of a lot more comfortable.

Another revelation I discovered when we hit on the Keokuk and Weehawken was the longitude meridians on pre-nineteen century nautical charts run 400 yards west of present day charts. A difference probably due to today’s more accurate timekeeping. This becomes apparent if you compare 52 degrees north. It used to pass through Cummings Point. Now, even allowing for decades of erosion, it passes to the east in the channel waters.

No doubt the reason many of the wrecks around Charleston had not been found was because of this quarter mile discrepancy.

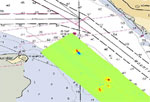

Relying on the mini-ranger, we painstaking blocked off a grid over the Keokuk’s position and found nothing. This failure to find any sign of the ironclad seemed unacceptable. I had overlaid and traced the eastern shore of Morris Island, measuring the erosion over 140 years. The light house that once stood on land now rose out of the water 400 yards from shore. And yet, judging the distance of our search area from the lighthouse by eye, it struck me that the beach seemed too far away from where Boutelle marked the Keokuk.

I instructed the mini-ranger operators on shore to take us directly over the supposed site on a course due west toward the island. Then, when I gave the word, we would turn and begin another grid search.

One hundred yards, two hundred. The guys in the van kept asking me when we were going to turn. Three hundred. The lighthouse loomed nearer. Finally, at three hundred and sixty yards I gave the order to swing around on a reverse course. Then the Schonstedt gradiometer sang.

We struck the Keokuk in the turn.

We then moved to the Weehawken’s marked position and applied the same maneuver and found her three hundred and twenty yards to the west of where Boutelle said she rested.

Applying the same data, we also homed in on the Stonewall Jackson, Norseman, Ruby, and the Raccoon, which Boutelle mislabeled the Georgiana.

If you should find yourself in Charleston and wish to research the naval actions and later disposition of sunken ships, be sure to read Benjamin Maillefert’s diaries in the Charleston city archive in the Fireproof Building. He salvaged most all the wrecks in the area and provides fascinating insight on the operations. It was one his references that showed me the wreck marked as the Georgiana was actually the blockade runner Raccoon.

Though we failed to find the Hunley again, we hardly left Charleston empty handed. A good time was had by all and we made a number of interesting discoveries.

Finds are recorded below in nautical positions in case later expeditions do not use mini-ranger coordinates.

KEOKUK

About three quarters of a mile east and slightly north of the old lighthouse. Four feet under silt, lying north and south.

32 41′ 44″

79 51′ 54″

WEEHAWKEN

Famous monitor, only one to fight and capture another ironclad: the CSS Atlanta. Seems quite broken up at least eight feet under silt. Lying on slight angle north and south.

32 43′ 02″

79 51′ 11″

PATAPSCO

Sunk by Confederate mine between Forts Sumter and Moultrie. Sitting upright in scoured channel at forty feet. Easily dived.

32 45′ 12″

79 51′ 58″

ACTEON

Heavy mag readings over site were British frigate was burned and sunk in 1776.Short distance from Patapsco.

32 44′ 48″

79 51′ 44

RUBY

Confederate blockade runner run aground off Folly Island.

32 40′ 57″

79 53′ 03″

RACCOON

Confederate blockade runner, sunk west of present day jetty. Mislabeled on old charts as Georgiana.

32 44′ 35″

79 50′ 10″

RATTLESNAKE

Confederate blockade runner destroyed few hundred yards southeast of Breech Inlet.

32 46′ 25″

79 48′ 13″

STONEWALL JACKSON

Confederate blockade runner run aground and burned. Now eighteen feet under the beach on Isle of Palms just south of the dunes at the end of either 24th, 25th, or 26th streets. Sorry about that. I marked the position but not the street. My hope is that someday the city or state will excavate her. One of the luckiest finds I ever made. By extreme luck I set the gradiometer right on top of the wreck in the first five minutes as I tried to adjust the instrument.

32 46′ 42″

79 48′ 03″

NORSEMAN

Blockade runner run high and dry in 1865. Now about a hundred yards from the beach.

32 47′ 23″

79 46′ 10″

HOUSATONIC

The Union sloop-or-war sunk by the Hunley. Has the sad distinction of being the first warship ever sunk by a submarine. Her scattered debris lies in the vicinity of…

32 43′ 07″

79 48′ 17″

CHARLESTON & CHICORA

Confederate ironclads. Anchored side by side in the channel, they were blown and sunk when the city fell to Union troops. I pinpointed their final position, but a search turned up nothing. The site has been heavily dredged by the Army Corp of Engineers over the past century, and as with so many other historic ships they have been dredged out of existence. They were last recorded at…

32 47′ 29″

79 55′ 21″

PALMETTO STATE

Confederate ironclad blown and sunk the same time as the Charleston and the Chicora. We had a very heavy strike along side and under the docks between warehouse #8 and the warehouse next door to the south. This site should definitely be surveyed. Benjamin Maillefert states in his diaries that he didn’t salvage the Palmetto State as heavily as he did the other shipwrecks.

32 47′ 47″

79 56′ 22″

GREAT STONE FLEET

A fleet of whalers, some quite famous, one or two dating from the Revolutionary War, deliberately scuttled by Union Navy to block entrance to Charleston Harbor. The project failed due to worms attacking the exposed hulls and the weight of the stone ballast pushing the ships deep into the soft silt. We received many strikes in the area where they sank, but dives found nothing protruding.

32 39′ 55″

79 50′ 20″

SWAMP ANGEL

Site of famous cannon that fired on Charleston before exploding is still discernable on Bass Creek due to vegetation.

32 43′ 10″

79 53′ 25″

WEEHAWKEN’S TORPEDO RAFT

During the battle of Charleston between Admiral Dahlgren’s monitor fleet and the Confederate forts, the Weehawken led the Union squadron into the harbor with a huge wooden anti-mine raft attached to its bow. The weight and drag made the monitor completely unmanageable and the raft was cast adrift. Although it’s been sitting in the reeds along the north bank of Bass Creek all these years, we were the first to identify it.

32 43′ 30″

79 53′ 25″

As of November, 1987, I or my NUMA crew have not returned to Charleston. But someday I may come back with our side scan sonar to survey the harbor. I’ve always suspected the Confederate’s floating battery, used against Fort Sumter in the opening shots of the war, is lying somewhere northwest of Fort Johnson. And, of course, there is still the Hunley. It would be a shame not to make another attempt to find her. Who knows? With any luck NUMA might be able to add a nice postscript to the story.

More on the U.S.S. PATAPSCO

USS Patapsco, a 1335-ton Passaic class Union Navy monitor built at Wilmington, Delaware, was commissioned in early January 1863. Assigned to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, she took part in a bombardment of Fort McAllister, on Georgia’s Ogeechee River, on 3 March. On the 7th of April Patapsco joined eight other ironclads in a vigorous attack on Fort Sumter, off Charleston, South Carolina, and received 47 hits from Confederate gunfire during that day. Beginning in mid-July, she began her participation in a lengthy bombardment campaign against Charleston’s defending fortifications. This led to the capture of Fort Wagner, on Morris Island, in early September. Fort Sumter was reduced to a pile of rubble, but remained a formidable opponent.

In November 1863, Patapsco tested a large obstruction-clearing explosive device that had been devised by John Ericsson. Remaining off South Carolina and Georgia during much of 1864 and into 1865, the monitor, or her boat crews, took part in a reconnaissance of the Wilmington River, Georgia, in January 1864 and helped capture or destroy enemy sailing vessels in February and November of that year. The Patapsco fought throughout the siege of Charleston. On 14 January 1865, while participating in obstruction clearance operations in Charleston Harbor, USS Patapsco struck a Confederate mine and sank in the channel off Fort Moultrie in 1865. Sixty two of her crew were lost.

While the location of Patapsco was thought to be known, no one had certified the remains until NUMA documented the location.

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design