U.S. Life Saving Service Saves Survivors By Land Not Sea

The schooner E.S. Newman in distress. Credit: Pea Island Preservation Society

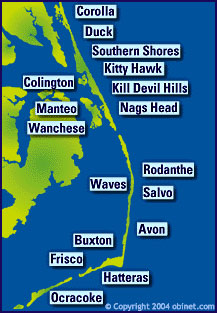

The elegant three-mast cargo carrier, its sails blown away, was caught in a raging hurricane that was sweeping the east coast of the United States. That it was in the confines of North Carolina’s renowned “Graveyard of the Atlantic” added to its woes. En route from Providence, Rhode Island to Norfolk, Virginia, to pick up a load of coal, the ship drifted almost 100 miles in powerful winds and torrential rains before running aground south of Pea Island, Rodanthe, on the Outer Banks.

The E.S. Newman was grounded off Pea Island, Rodanthe, N.C., Outer Banks. Credit: N.C. Dept. of Tourism

At the Pea Island Station Number 17, Officer Theodore Meekins was on watch duty at seven p.m. when the rain let up, leaving dark clouds on the horizon. That’s when he spotted a rocket high in the sky coming from the south. He quickly sent one up in return, acknowledging what might be a call for help from someone down the coast. When he reported it to Capt. Richard Etheridge, little did Meekins know he would be playing a major role in one of the most daring rescue attempts ever made by the service.

Etheridge was appointed head station keeper in 1880. A former U.S. Army sergeant, he proved to be exceptional at his job. He was hard-nosed, but respected by his men who worked diligently under his direction. He hired a crew composed of veterans with whom he had served. None of them were surprised when their leader ordered hundreds of pounds of equipment loaded into a beach cart for immediate deployment on what became a two mile trudge in wet sand.

Wind and waves prevented the use of the breeches buoy. Credit Pea Island Preservation Society

Patch from U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Richard Etheridge, built in honor of the heroic captain.

Credit: USCG

But there’s more to the story. Capt. Etheridge and all of his men were black. The superintendent of the service knew of his impeccable military achievements and hired him. He was told to choose an all black crew. In those days, it was difficult for blacks to be hired for responsible jobs. But it didn’t take long for this crew to prove they were the best, making hundreds of rescues in some of the most treacherous waters along the coast. They risked their lives to save others regardless of race. As the late radio broadcaster Paul Harvey said: “Now you know the rest of the story.”

Patch honors the men of the Pea Island Lifesaving Service Station 17. Credit: Pea Island Preservation Society

Note: The saga of the brave captain and his crew continues thanks to the Pea Island Preservation Society that offers visitors an opportunity to relive the days of Station 17. The original cookhouse is now a museum in Manteo, Roanoke Island, North Carolina. It commemorates the dedication and service the Pea Island lifesavers contributed to the history of our country. On display are the original signboard from the E.S. Newman, photographs, records and other memorabilia from the station. For details of operation go to: peaislandpreservationsociety.com or call: (252) 573-8332.

The Pea Island Cookhouse Museum, Manteo, Roanoke Island, N.C. Credit: Pea Island Preservation Society

Special thanks to Darrell Collins, President of the Pea Island Preservation Society, for recounting the history of the rescue and the U.S. Lifesaving Service.

Author: Ellsworth Boyd

Ellsworth Boyd, Professor Emeritus, College of Education, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, pursues an avocation of diving and writing. He has published articles and photo’s in every major dive magazine in the US., Canada, and half a dozen foreign countries. An authority on shipwrecks, Ellsworth has received thousands of letters and e-mails from divers throughout the world who responded to his Wreck Facts column in Sport Diver Magazine. When he’s not writing, or diving, Ellsworth appears as a featured speaker at maritime symposiums in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, New York and Philadelphia. “Romance & Mystery: Sunken Treasures of the Lost Galleons,” is one of his most popular talks. A pioneer in the sport, Ellsworth was inducted into the International Legends of Diving in 2013.

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

0 Comments