Germany’s High Seas Fleet Rests in Scapa Flow

German ships anchored at Scapa Flow before the scuttling

When warships sink, it’s usually during a battle where they’re shelled, torpedoed, bombed or rammed and heroic deeds are recorded in history books. But not so heroic, and surely distressful for the captains, is when they have to scuttle their ships. Such was the case in the scuttling of the German ships in Scapa Flow, Scotland, one of the most extraordinary sagas in the history of naval warfare.

Following the WWI armistice in November, 1918, a large number of ships in the German High Seas Fleet were interned in a sheltered bay the Scots called the “Flow.” Meanwhile, the Treaty of Versailles was taking months to settle. Finally signed on June 28, 1919, it ended the conflict between Germany and the Allied Powers. (France, Russia, Great Britain, Japan, Italy and the United States).

Angry and despondent over not being informed of his fleet’s fate, Rear Admiral Ludwig Von Reuter devised a secret code for the scuttling. His orders, given a week before the treaty was signed, coincided with the changing of the guard aboard British surveillance ships. Nearly everything went as planned as 52 of the 74 interned warships sank to the bottom of the Flow and 22 were beached by Royal Navy boarding parties. Nine German sailors died and 16 were wounded. Ironically, the whole scenario might have been avoided if the treaty had been sealed much earlier as originally planned.

One of the best books published about the scuttling, Credit: Orkney Pres, Orkney Isles and Diverse Travel, Danbury, Essex, England

In his book, The Wrecks of Scapa Flow, Orkney Press, 1985, author David Ferguson recounts some of the experiences of those who were present when the ships went down. One story, told to a local newspaper editor by the late Ivy Scott, then an 18-year-old girl from a school in Stromness, Orkney, Scotland, captures the drama of the moment. She and 150 students from various grade levels were visiting the Flow on a field trip.

“It was a good day for the trip,” she said, “with a light breeze, bright sun and calm waters. We, the students and teachers from the Stromness Academy, set sail on the Flying Kestral which was a nice boat for touring. One boy in our group loved ships and shouted out the name, tonnage and fire power of each vessel as we passed them. We were all enjoying the ride and eating sweets when suddenly our Union Jack flags came down and German Eagle ones were hoisted on the ships about to be scuttled. Then all around us the great ships began to sink. Some went down on an even keel and others upended, plunging quickly in a wash of waves. German sailors either swam ashore or were rescued by British seamen. Our boat returned to Stromness under full steam. We got home safely and I’ll never forget my adventure in the Flow.”

Scapa Flow, a strip of land between Scapa Bay and the town of Kirkwall, forms a natural harbor in the Orkney Isles off the northeast coast of Scotland. Used as an anchorage since the days of the Vikings to the present—where tankers now load North Sea oil—it was a significantly strategic location during two world wars. Universally recognized as a military destination where thousands of servicemen and women passed through, the Flow gained more notoriety when it became one of the world’s topnotch wreck diving destinations.

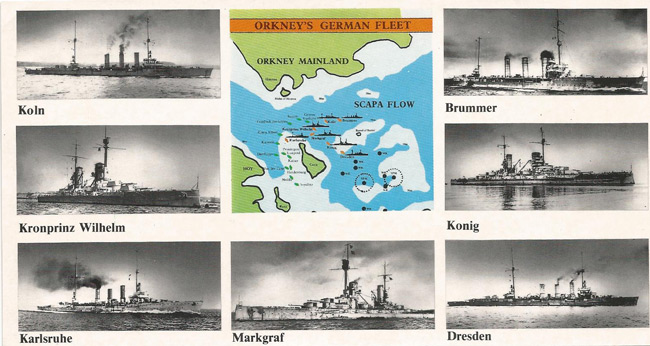

By October, 1939, a little over a month after the outbreak of WWII, most of the major remains of the German High Seas Fleet had been raised or scrapped. Fortunately, seven of the ships—four cruisers and three battleships—were left and became historical monuments in a diving mecca. The cruisers all rest on their sides in waters somewhat shallower than the battleships. Nearly 400 feet long, the 6,190-ton SMS (Seiner Majestat Schiff… in English His Majesty’s Ship) Dresden was the leader of these lighter vessels. It lies on a slope 85 to 120 feet deep, partially covered by sand on what remains of its superstructure. When the forward deck collapsed, little could be identified except a bathtub sitting in the sand. The ship is still armed with its 5.9 inch guns which house small fry that attract large schools of mackerel. The 460-foot SMS Brummer, registered as a mine laying light cruiser, has a partially intact bridge with some of its brass still showing. Divers peer into the engine room at 115 feet, but hanging debris deters entry. Schools of codfish are attracted to the wreck and can be spotted cruising the perimeter. The cruiser SMS Karlsruhe is the shallowest dive at 50 to 100 feet. It still has its armored control towers that served as command posts during battle. The 367-foot warship has a broken bow, but its anchors, chains and capstans remain in place. The SMS Koln (also named SMS Coln) is nearly 500 feet long and remains a favorite dive among the cruisers. Pitched to its starboard side and well preserved, its bow is covered with sea anemones. Crabs and starfish cling to the hull not far from 5.9-inch guns that point out to sea. On a 75 to 100-foot descent, the SMS Coln provides one of the few spots where divers can get a glimpse of the control tower, bridge and engine room. Some of its portholes, lifeboats and davits remain attached to the collapsed deck.

Map of Scapa Flow and its seven ships before sinking, Credit: Charles Tait, St.Ola, Orkney Isles

The battleship SMS Konig was a forerunner in the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Fought off the North Sea coast of Denmark, it ended in a draw but enabled England to keep Germany out of the Atlantic Ocean and away from the shoreline. Although part of it was dynamited, the 575-foot behemoth retains its 12-inch thick amour casing and 40,000 HP engines. It was one of the first ships to mount 12-inch guns where large pollack school in 75 to 140-foot depths. The 28,000-ton SMS Markgraf was one of the most powerful German battleships equipped with 12-inch guns capable of striking targets 13 miles away. Settled at 145 feet, deepest of the Flow wrecks, it rolled as it sank. The starboard side is buttressed by its gradually deteriorating superstructure. Gun barrels and tangled machinery greet divers along the 480-foot stretch of steel covered by kelp and dead man’s fingers coral. The SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm is a favorite wreck for wrasse that feed on shrimp and sea urchins clinging to the 580-foot battleship. Resting in the sand keel up, its main armaments are still intact. Divers favor the varied skill levels offered in waters 60 to 130 feet deep. Some like to follow a guide who leads them down under the ship where their lights reveal well preserved guns and their housings.

Visitors to Stromness, second largest town in the Orkney Isles and kicking off point to the Flow, delight in a visit to the local museum. Run by the Orkney Natural History Society, it features displays dedicated to the isles’ seafaring history. Exhibits include munitions, armaments, personal belongings and other relics from the British and German fleets. While the Stromness Museum remains a “must see” for divers, so is the one in nearby Hoy. Only a 10-miute ferryboat ride from Stromness, the Lyness Naval Base Visitors Center and Museum is run by the Orkney Islands Council of Museum Services. Displays include German guns, uniforms, naval insignia and ship models. Touch screen narratives and personal tours add to the museum’s appeal.

Scapa Flow is not just an underwater attraction which became Europe’s largest shipwreck graveyard. For centuries it played a major role in travel, trade and conflicts. One of the greatest natural anchorages in the world, it was capable of harboring a number of navies, one of which decided it would remain there permanently.

Author: Ellsworth Boyd

Ellsworth Boyd, Professor Emeritus, College of Education, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, pursues an avocation of diving and writing. He has published articles and photo’s in every major dive magazine in the US., Canada, and half a dozen foreign countries. An authority on shipwrecks, Ellsworth has received thousands of letters and e-mails from divers throughout the world who responded to his Wreck Facts column in Sport Diver Magazine. When he’s not writing, or diving, Ellsworth appears as a featured speaker at maritime symposiums in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, New York and Philadelphia. “Romance & Mystery: Sunken Treasures of the Lost Galleons,” is one of his most popular talks. A pioneer in the sport, Ellsworth was inducted into the International Legends of Diving in 2013.

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

0 Comments