Steven Spielberg’s Shipwreck Hoax

Producer, director and writer Steven Spielberg placed the SS Cotopaxie in the Gobi Desert in one of his Sci-fi films. Credit; Universal Studios

Truth is the Cotopaxi, named after a volcano in Ecuador, was lost in a fierce storm off St. Augustine, Florida, December 1, 1925. It was one of 17 Emergency Fleet Corporation steamships built in 1918 to carry supplies to our troops during WWI. Unfortunately, by the time the supply ship was launched and sailing, the war was over and it became one of the peacetime fleet of the U.S. Merchant Marine Service. Designated a “bulk carrier,” it was transporting 3,800 tons of coal from Charleston,South Carolina to Havana, Cuba, when it foundered 35 miles off the Florida coast. Its ship to shore mayday message, “in distress,” which went directly to a station in Jacksonville, Florida, was never acknowledged. Actual records today show the date the ship sank and its location. It had been at sea for two days before the storm hit, taking the lives of its captain and all 31 of his crew. There were no survivors and no other ships at sea received the message from the stricken ship. No wreckage, lifeboats or personal belongings ever washed ashore.

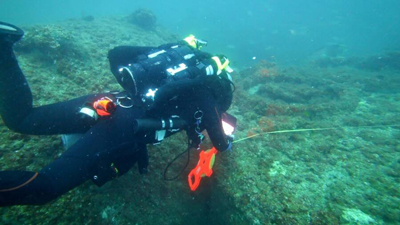

Michael Burnette takes measurements to try and identify the wreck. Credit: Science News

Burnette has the experience and credentials to back up his convictions. He has collaborated in identifying more than two dozen Florida shipwrecks including the tanker, Pan Massachusetts, the steamer Peconic and the luxury yacht Nohab. A St. Petersburg, Florida, resident for over 20 years, Burnette’s work is highly regarded at the National Fisheries Institute, where he serves as a marine biologist. He heads two programs, one designed to save and protect sea turtles and another one to investigate a newly discovered species of coral. After years of contemplating the fate of the Cotopaxi, he dug in as deeply as he could and formed a conclusion in February, 2020, of what happened to Spielberg’s ghost ship nearly 100 years ago.

The SS Cotopaxie disappeared without a trace off Florida shores in 1925. Credit: Mariner’s Museum

A windless, broken free from the bow, sits alone on the sandy bottom. Credit: Science News

His research, mapping, measuring and exploration complete, Burnette is convinced the Bear Wreck is the SS Cotopaxi. Everyone involved agrees and the mystery, instigated by a Hollywood blockbuster film, is finally solved. Burnette concluded, “A lot of times these discoveries are very emotional, especially when you get the feeling that your theory is correct. It’s an emotional rollercoaster as you realize this is the final resting place of a captain and his crew that went down with their ship. There are still a few relatives remaining that we are reaching out to in hopes of giving closure to their long and arduous delay to discover the truth.”

Author: Ellsworth Boyd

Ellsworth Boyd, Professor Emeritus, College of Education, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, pursues an avocation of diving and writing. He has published articles and photo’s in every major dive magazine in the US., Canada, and half a dozen foreign countries. An authority on shipwrecks, Ellsworth has received thousands of letters and e-mails from divers throughout the world who responded to his Wreck Facts column in Sport Diver Magazine. When he’s not writing, or diving, Ellsworth appears as a featured speaker at maritime symposiums in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, New York and Philadelphia. “Romance & Mystery: Sunken Treasures of the Lost Galleons,” is one of his most popular talks. A pioneer in the sport, Ellsworth was inducted into the International Legends of Diving in 2013.

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

0 Comments