Tankers and Freighters Were Sitting Ducks in Graveyard of the Atlantic: Part II

They’re everywhere, a ubiquitous conglomeration of lost ships the likes of which will never be matched by any other nautical graveyard. The ships, their masters and crews plunged to the bottom of North Carolina’s Graveyard of the Atlantic where a seafarer once declared: “It’s a place to sail, troll and dive, a place where only fish survive, a place that fosters all our fears, a place that harbors a widow’s tears.”

They’re everywhere, a ubiquitous conglomeration of lost ships the likes of which will never be matched by any other nautical graveyard. The ships, their masters and crews plunged to the bottom of North Carolina’s Graveyard of the Atlantic where a seafarer once declared: “It’s a place to sail, troll and dive, a place where only fish survive, a place that fosters all our fears, a place that harbors a widow’s tears.”

There were many widows from the long list of seamen who went down with their ships during WWII: Dixie Arrow, Proteus, Byron D. Benson, Norvana, Naeco, Empire Gem and many others. More than 100 U.S. and Allied vessels were sunk by a bevy of Nazi U-boats roving in “wolf packs.” Others struck mines, shoals or were lost in violent storms. Our ship losses were the worst in American history and would have increased if we hadn’t hastily developed effective anti-submarine weaponry.

Allied tankers and freighters were sitting ducks for German U-boats. Credit: National Archives

Tankers and freighters were sitting ducks in the east coast shipping lanes, especially at the beginning of the war when we had only five sub-chasers, a handful of aircraft and an unconventional collection of assorted small craft that could act only as rescue vessels. Unfortunately, we didn’t order a blackout until we were three months into the war. By then, 50 large ships met their fate from marauding German U-boats. One of the first to go was the Alan Jackson, torpedoed off Cape Hatteras, January, 1942. The 4,000-ton tanker, transporting 72,000 barrels of crude oil from Cuba to New York City, was cruising in calm seas at 1:30 a.m. when she was struck by two torpedoes. The first one caused little damage smashing into an empty cargo hold, but the second one broke the ship in half when it struck the bow spilling thousands of gallons of oil into the sea. Some of the crewmen were trapped below deck while others were swept into the churning waters. The captain, trapped in his burning quarters, escaped through a porthole. All of the survivors faced three dangers: drowning, burning to death or being sucked into the propeller which was still turning. Thirteen out of 35 survived and were rescued by the destroyer USS Roe. Sunk on the edge of the Gulf Stream, the Alan Jackson has never been found. She was one of 17 ships lost in January and February, 1942, in what newspapers called, “The Battle of Torpedo Junction.”

By March, the U-boats had organized their wolf packs that rested on the sandy bottom by day, while preying upon vessels in the shipping lanes at night. The 220-foot, 500-ton “iron coffins” had four torpedo tubes forward and one aft, 14 torpedoes and two deck guns. Night attacks were frequent as unwary ships were silhouetted against the lights on shore. Until the end of March, when the blackout was finally ordered, U-boats sank an average of almost one ship daily.

The Caribsea was sunk at night and sank 15 miles east of Ocracoke. Credit: Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Va.

One of the ships sunk in March was the American cargo vessel Caribsea, now a popular dive site for charter boats from Beaufort and Morehead City. Carrying a valuable cargo of manganese ore, the 251-foot lake freighter was sunk at night, southeast of Ocracoke, between Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout. Her memory lives on today in the Ocracoke United Methodist Church where a gilded cross, made from salvaged wreckage of the Caribsea, rests near the altar. Among other remains that washed ashore was the maritime license of engineer James Gaskill who was lost in the attack.

A week later, March 18, 1942, Nazi U-boats hit the jackpot sinking five ships in one night: the tankers Papoose, W.E. Hutton, E.M. Clark and the freighters Liberator and Kassandra Louloudis. The 5,240-ton Papoose rolled over and sank after she was torpedoed amidships by the U-124. Some of her crew escaped and rowed ashore in the pale light cast by the flickering fires aboard the W.E. Hutton which was torpedoed by the U-124 after it victimized the Papoose.

The Papoose, sunk 17 miles off Cape Lookout, is partially intact, but leans so far to port she appears to be upside down. The keel is the highest part of the wreck in 75 feet of water while the deeper lower decks have passageways accessible to experienced divers. The W. E. Hutton, 16 miles from Cape Lookout, rests at 60 feet, split in two sections about 400 yards apart. A year after she was torpedoed, the partially submerged remains of the tanker were struck by the Suloide, a small cargo vessel transporting manganese ore. It sank in 60 feet of water, while the W. E. Hutton was depth charged later as a navigational hazard. Divers get a special treat diving on both of the vessels which are not far apart. Charter boats reach them sooner, each being not as far offshore as some of the other wrecks.

Small fry school over bow of the Caribsea. Credit: North Carolina Travel & Tourist Board

The Atlas, a 7,137-ton tanker sunk by the U-552 when it was on a three day spree along the eastern side of Lookout Shoals, rests near the Caribsea 120 feet deep. Rising 80 feet from the bottom, she’s not hard for captains to locate after traveling 27 miles out of Beaufort Inlet. Divers love the John D. Gill which is overrun with schools of oceanic pelagic fish and other marine life. One of the largest tankers sunk off the Outer Banks, the 12,000 ton mammoth was almost brand spanking new when she went down. President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal to boatswain Edwin Cheny for his heroic feat during the sinking of the ship. Cheny launched a life raft and maneuvered it through a pool of burning oil by swimming underwater while towing it behind him. He surfaced with severe burns on his face and arms, but still managed to help six of his shipmates to the raft. All were rescued later.

Twenty-four miles from the tip of Capt Fear, the John D. Gill is an ideal site. Her main deck is at 45 feet, while the bow—sitting upright—is 90 feet deep. The 544-foot tanker is broken in half with a feature divers sometimes miss. The gun deck is upside down with the gun acting as a support beneath it. Dive Masters usually point it out when circling the site.

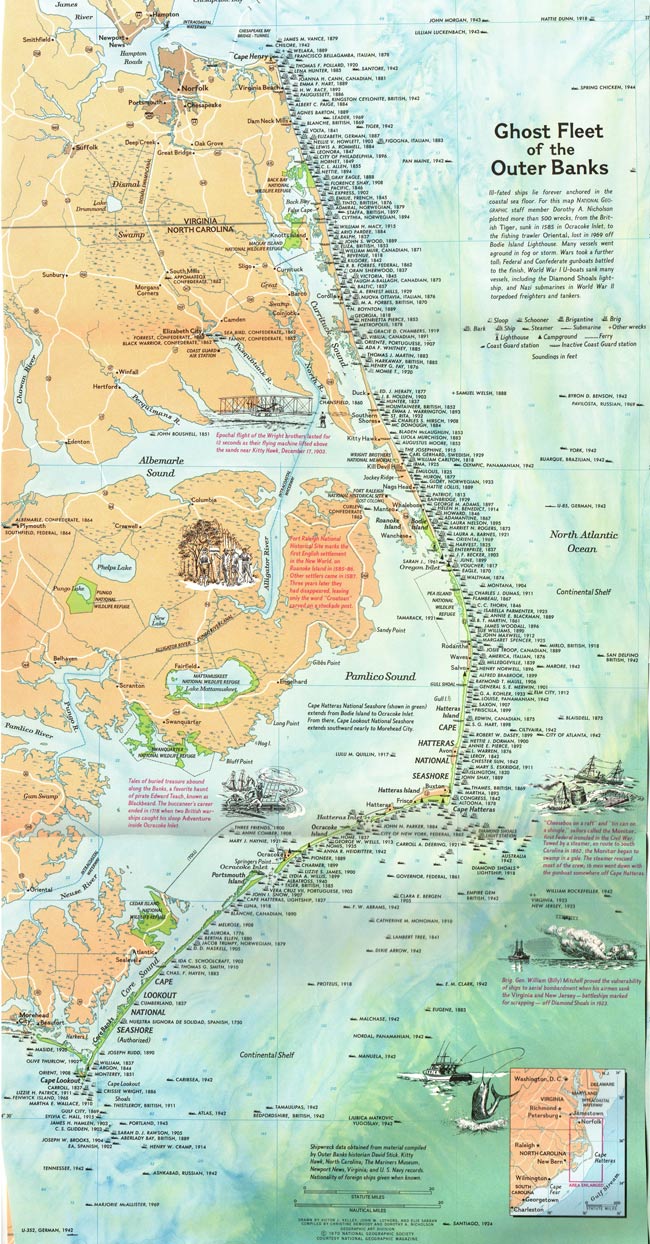

So they rest, over 2,000 of them off a 250 mile stretch of shoreline and islands of the Tar Heel State. The wartime ones are monuments to time, the remains of battles won and lost. They’re in an eternal grave that divers still explore…. victims of the Third Reich’s futile attempt to conquer the world.

Map shows some of the thousands of ships sunk in the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Credit: North Carolina Travel & Tourist Board

Next Month: Graveyard of the Atlantic–The Blockage Runners

Author: Ellsworth Boyd

Ellsworth Boyd, Professor Emeritus, College of Education, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, pursues an avocation of diving and writing. He has published articles and photo’s in every major dive magazine in the US., Canada, and half a dozen foreign countries. An authority on shipwrecks, Ellsworth has received thousands of letters and e-mails from divers throughout the world who responded to his Wreck Facts column in Sport Diver Magazine. When he’s not writing, or diving, Ellsworth appears as a featured speaker at maritime symposiums in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, New York and Philadelphia. “Romance & Mystery: Sunken Treasures of the Lost Galleons,” is one of his most popular talks. A pioneer in the sport, Ellsworth was inducted into the International Legends of Diving in 2013.

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Mr. Boyd,

Thanks for keeping some of the maritime history of WW II alive and relevant. My comment to Part I seems to have disappeared into cyberspace, but I have enjoyed both articles immensely. Documenting the ravages of war underlines the enormous sacrifices made by those who served so unselfishly.

Rick: Thanks for your comment. I’ll check with the Webmaster to see what happened to your comment on Part I of the Graveyard of the Atlantic and my response to it. Both are gone.

Yes, isn’t it amazing the sacrifices made during WWII, much of it beginning with the torpedoing of the innocent tankers & freighters sailing their regular routes off the N. Carolina coast. Much of this is not included in the history books. I’m gad you enjoyed my article. I hope others will read it.

Hi Dr. Boyd,

I have been trying to get in contact with you or someone from NUMA for a podcast interview opportunity. My e-mails to the NUMA accounts have been getting bounced back.

I would love to get in contact with someone if there is any interest.

Thank you,

Mike Sullivan

Mike: Feel free to contact me at: ellsboyd@aol.com

I will try to help you. Ellsworth