The SS Byron D. Benson: Reluctant Prey in Torpedo Junction

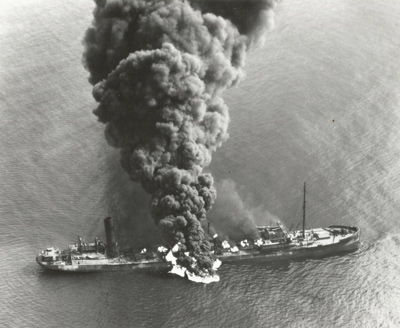

Smoke pours from deck of Bryon D. Benson which burned for three days before sinking. Credit: Mariners Museum, Newport, News, Va.

The SS Byron D. Benson is more than just another tanker sunk off North Carolina in the early stages of WW II. The 7,953-ton, 465-foot Tidewater Oil Company ship did her best to avoid sinking in Torpedo Junction where so many other American and Allied vessels were victimized by German U-boats. The tanker fought so hard to stay afloat after taking a torpedo on its starboard side amidships, it wasn’t until three days later that she plunged to the bottom in 110 feet of water, 28 miles northeast of Oregon Inlet off Nags Head, North Carolina.

The dramatic aerial photo of the ship, black smoke pouring from her deck, appeared in newspapers throughout the world in 1942, prompting our country’s war effort to speed up anti-submarine warfare and the American public to be more determined than ever to fight the Nazi menace. Captain Erick Topp, the “take no prisoners” commander of the –U-552, not only targeted the Benson, but also sank the British Splendor, Atlas, and Tamulipas, all off the coast of North Carolina, in what became known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Topp, the third most successful German submarine officer of the war, later denounced for ordering his deck gunners to shoot the survivors of foundering ships, sank 34 American and Allied vessels from three different submarines he commanded.

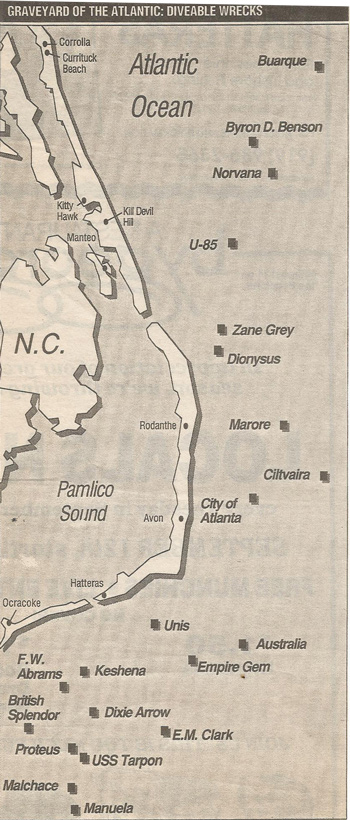

Map show location of Byron D. Benson off Kill Devil Hills, Nags Head, NC

Although divers have explored the Benson for years, it remains one of the best kept secrets off the North Carolina coast as other shipwreck buffs flock further south where the Tarheel State’s waters are warmer. Picture if you will, a mammoth wreck stretching the length of one and a half football fields, resting upright on the bottom with some of its machinery still intact. Although much skeletal debris remains, interspersed with rusty, coral covered transport pipes, the cabin and holds that haven’t caved in are penetrable. Time has taken its toll and parts of the wreck that used to be fun to explore are no longer safe.

Actually, there’s so much to see on the outside, going inside isn’t necessary. Veteran wreck diver and marine historian Bill Hughes of State College, Pennsylvania, says, “I love to use the variety of machinery, enticing hatchways and huge valves as backdrops for my photos. Salvors occasionally score a brass goodie on this wreck that’s good for novice divers as well as experienced ones. One new diver said that when he first saw the ship sitting erect on the bottom, it looked like something out of a Hollywood movie set.

The actors are there in droves, darting in and out among the boilers, pipes, chains and rubble. A grouper or a lobster could be holed up in a crevice where a flounder might be partially buried in the sand nearby. Schools of amberjack and dolphin glide in from deep water mingling momentarily with the small fry and other migratory species that frequent the site. Although the water may reach 80 degrees on the surface in mid-summer, it drops 20 degrees on the bottom, requiring a full wet suit or a dry suit for complete comfort. Visibility averages 10 to 15 feet, but might increase to 50 feet on especially good days. The main deck can be explored at 70 to 80 foot depths.

Divers approach wreck of Byron D. Benson Credit: Bob Allen

A slight list to the starboard side of the wreck is indicative of the hit it took from the U-552. Although Capt. John McMillan of the Benson was aware of danger while cruising through Torpedo Junction, he alternated speeds and zigzagged on a course that might have helped his ship remain an evasive target. He also had a cordon of two vessels accompanying him, a tanker—the Gulf of Mexico and an armed British trawler—the HMS Norwich City. Of the three lookouts on the tanker, a seaman on the bow and the captain and third mate on the bridge, none realized the escort vessels had slipped away far to the stern of the targeted ship.

The long, low to the water tanker, loaded with thousands of barrels of crude oil bound from Port Arthur, Texas, to Bayonne, New Jersey, was a sitting duck. At 9:40 p.m., a lookout aboard the submarine spotted the Benson running with its lights out, silhouetted against a bright western sky. As the torpedo struck its prey amidships, it blew a large hole from below the water line to the main deck spewing fire, smoke and oil everywhere. Lifeboats number one and three, secured on the starboard side of the ship, were engulfed in a sea of blazing oil. But the chief engineer and 26 crew launched lifeboat number four from the port side. Another member of the crew missed the lifeboat, but launched a raft and escaped unharmed. Yet the same can’t be said for the captain and eight remaining crew who set afloat in another lifeboat. While pulling away, all aboard were engulfed by burning oil and lost at sea. The 27 men in the original lifeboat were rescued by the destroyer USS Hamilton two hours after the attack. The lone sailor in the other lifeboat was picked up by the HMS Norwich City. Meanwhile, the burning tanker became a reluctant victim. Amid the confusion of death and destruction, the captain and crew failed to shut down the ship’s engines, creating what one sailor called “a voyage to hell.” On April 7, 1942, three days after the hit, the SS Byron D. Benson became another casualty in Torpedo Junction.

Note: Byron D. Benson was the founder of Tidewater Pipe Company which became Tidewater Oil (opening Tydol Service Stations) and later was bought out by Standard Oil Company. In 1879, Benson was credited with running the world’s first oil pipeline through the Allegheny Mountains. It snaked from Coryville to Williamsport, Pennsylvania, a distance of 109 miles. In 1920, the pipeline pioneer added one more tanker to his fleet of four vessels and named it after himself. Using tankers and pipelines, Standard Oil became a world distributor of crude oil. Benson died in 1888 at age 55.

Author: Ellsworth Boyd

Ellsworth Boyd, Professor Emeritus, College of Education, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, pursues an avocation of diving and writing. He has published articles and photo’s in every major dive magazine in the US., Canada, and half a dozen foreign countries. An authority on shipwrecks, Ellsworth has received thousands of letters and e-mails from divers throughout the world who responded to his Wreck Facts column in Sport Diver Magazine. When he’s not writing, or diving, Ellsworth appears as a featured speaker at maritime symposiums in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, New York and Philadelphia. “Romance & Mystery: Sunken Treasures of the Lost Galleons,” is one of his most popular talks. A pioneer in the sport, Ellsworth was inducted into the International Legends of Diving in 2013.

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Impressive account of the unfortunate sinking of this tanker and loss of life. I’m glad that you were able to provide details of its mission and of the crew. We too often forget about the people who bravely did their duty under some very trying conditions. Thanks for the article.

Rick

Thanks very much for your kind comments. Yes, you are right about how history neglects telling the stories of the crew and others who perish in shipwreck disasters. This was an interesting tale in that the vessel sailed on fire for three days before it sank. It was sad what happened to the captain and many of his crew. I have other interesting stories about shipwrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic which I will write about in the future.

The article about the Byron D. Benson is very interesting. I have one question. Shouldn’t the tanker have been better protected by the two escort ships? Thanks. I look forward to your next story.

I’m glad you liked the article. Research shows the weather turned bad. It was foggy. In the fog ships must be careful not to get too close to each other, especially if the seas are acting up. The submarine commander was smart. He didn’t hang around to try for a second hit. I guess he knew the escort ships would close in on him.