Lake Ontario’s Jefferson: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The Jefferson closely resembled clipper ships like the Pride of Baltimore II. Credit: Clipper City Museum

How would you like to suit up on shore, walk out 20 feet on a marina dock, jump into 12 feet of water, and explore the remains of the Jefferson, a 20-gun brig built during the War of 1812? That’s what Kevin Crisman and Art Cohn did on three different occasions spanning six weeks of archaeological excavation.

Crisman, a Professor of Nautical Archaeology, Texas A & M University, and Cohn, Founder and Senior Adviser of the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, completed a five year study of this elusive shipwreck and shared their findings with other historians. The Jefferson was the only known survivor from the naval fleet that patrolled the waters of Lake Ontario in a brief, indecisive struggle between England and the United States. (The War of 1812 lasted two years).

“The good part,” Crisman said, “was simply walking to the dive site and jumping in. The bad part was diving so close to the docks and boats. We scheduled our studies—in cooperation with marina personnel–in the early summer and late fall when the place wasn’t so busy. The ugly part was the wreck being in water so shallow, the timbers actually protruded above the surface. It nearly broke my heart when I heard that ice skaters had ripped some of the timbers off to fuel a fire on the shoreline so they could keep warm.”

Drawing depicts Commodore Thomas Mcdonough defeating the British in a hard fought battle on Lake Champlain. Credit: Lake Champlain Maritime Museum

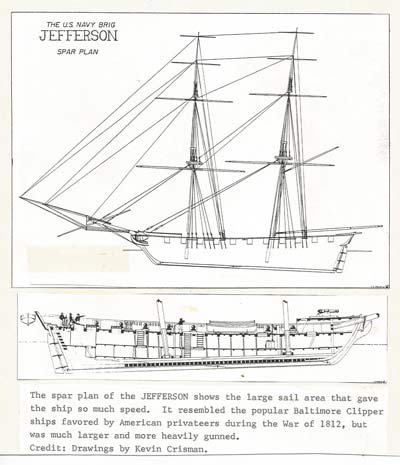

Located by Crisman and Cohn in shallow water of the Navy Point Marina, Sackets Harbor, New York, the historic brig was built by shipwright Henry Eckford who produced a succession of large, fast warships to counter the Royal Navy forces. Lake Ontario’s deep waters and vast surface area provided opportunities for maneuvering against an enemy squadron. This became Eckford’s inspiration for designing the Jefferson with a shallow draft and sharp hull for swift sailing. The hull closely resembled the streamlined Baltimore Clipper Ship designs favored by American privateers during the war.

Completed early in 1814, the size and presence of the Jefferson on Lake Ontario intimidated the British and held them at bay while other celebrated naval engagements were being fought. Earlier, Admiral Oliver Perry (“We have met the enemy and they are ours.”) forced the surrender of six British vessels which gave control of Lake Erie to the Americans. In September, 1814, the Jefferson’s contemporary brig, the Eagle, accompanied by the Saratoga, under the command of Commodore Thomas Macdonough, defeated an invading British force in a hard-fought battle on Lake Champlain. Meanwhile, all the Jefferson could muster was to accompany her sister brig, the Jones, in setting up a blockade of several British schooners moored in the Niagara River.

When the war ended late in 1814, an American squadron was laid up and left idle at Sackets Harbor. The Jefferson was one of them and sank at her mooring in 1818. By 1825, the other ships were sold to a salvor who converted a few of them into merchant craft and broke up the rest. Fortunately, Eckford’s 20-gun brig was left on the bottom of the harbor, destined to become part of a modern marina built in 1965. Although some of the marina’s pilings were driven through a few of the gun ports and part of the hull, many of the ship’s timbers, which were unusually large for a vessel of this class, remained intact. The hull’s starboard side and forward half of the keel were missing, but the port side remained well preserved beneath the lake bottom mud.

Among the artifacts discovered on the wreck was this flintlock pistol. Credit: Lake Champlain Maritime Museum.

Mapping, measuring and sketching the 123-foot long wreck, Crisman, Cohn and their team worked in waters that ranged from zero to 15 feet visibility with a daily average of three to four feet. Although he hoped to learn more about life in the 19th century, Crisman was pessimistic about finding artifacts since the ship was abandoned before it sank. But as work progressed, he was pleasantly surprised. The soft mud that settled throughout the interior of the port side contained ship and crew remains. The archaeological team salvaged flintlock pistols, military buttons, pearlware plates, British and American coins, pottery shards, London mustard bottles and kitchen utensils. One of the latter, a short handled spoon, became a prized discovery which authenticated the wreck as the Jefferson.

The spar plan of the JEFFERSON shows the large sail area that gave the ship so much speed. It resembled the popular Baltimore Clipper ships favored by American privateers during the War of 1812, but was much larger and more heavily gunned. Credit: Kevin Crisman

“Although we were almost sure it was the brig, Jefferson,” Crisman said, “there was a possibility it could have been the Jones which was built by the same shipwright. But when we found the spoon with the initials ‘I New’ scratched on it, we knew we were on the right ship.” Crisman had a list of the ship’s muster roll that included a crewman named James New. The “I” scored on the spoon was the archaic rendition of “J.” Thus James New, a sailor who defended his country over 200 years ago, helped modern-day archaeologists identify his ship.

Inspection of the hull revealed evidence of a high level of skill and craftsmanship by the builder and his workmen. Nearly all the primary structural members were fashioned from the finest white oak tightly fastened together with wrought-iron bolts and spikes. The care taken in finishing and fitting the ship led to one of the top achievements in the age of sail and, as the century progressed, paved the way for acclaimed designs and sailing technology.

Author: Ellsworth Boyd

Ellsworth Boyd, Professor Emeritus, College of Education, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, pursues an avocation of diving and writing. He has published articles and photo’s in every major dive magazine in the US., Canada, and half a dozen foreign countries. An authority on shipwrecks, Ellsworth has received thousands of letters and e-mails from divers throughout the world who responded to his Wreck Facts column in Sport Diver Magazine. When he’s not writing, or diving, Ellsworth appears as a featured speaker at maritime symposiums in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, New York and Philadelphia. “Romance & Mystery: Sunken Treasures of the Lost Galleons,” is one of his most popular talks. A pioneer in the sport, Ellsworth was inducted into the International Legends of Diving in 2013.

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Thanks again Mr. Boyd for another historical account of a sunken ship. The War of 1812 is often relegated to a point of little importance, but your story helps to flesh out encounters between the British and American forces. Thanks for illuminating this often dismissed piece of history.

Thanks very much for your comment. Yes, I agree that this war was relegated to a point of little importance. Had we lost some of the major battles, the war could have continued for a long time. There is a possibility too, that we could have been back under British rule.The heroes of this war never got the awards and acclaim they deserved.

Thanks for this page. Apparently, it’s been long enough that I have feelings of nostalgia about spending a week diving on the Jefferson* and otherwise helping Kevin and Art with their project. However, it hasn’t been long enough for me to forget how boring the work is for someone who isn’t a nautical archaeologist. Lying on the bottom in 12 feet of water for two hours, measuring gunports and trying not to stir up the mud, is less than thrilling. I have to commend their patience and persistence, as long as I’m not compelled to exhibit those traits myself.

I also spent a day helping with the Eagle in the Poultney River, south of Lake Champlain. I guess the visibility was about a foot. I dropped a clipboard in six feet of water and spent five minutes finding it again. Kevin has written an excellent book, “The Eagle” about it.

*Unless there was an additional ship under the docks at the marina that Art and Kevin worked on. I vaguely remember the name of the ship as Jefferson, but somehow confused its dimensions with the two very large (for the time) warships that were built at Sackets Harbor.

Thanks for sharing your experience diving with Kevin and Art. You all did well in some tough conditions. Finding the spoon was serendipity. It surely helped in identifying the wreck. The other artifacts were interesting as well. I will have to look up Kevin’s book on the Eagle. Thanks again.

Best regards, Ellsworth Boyd