Terror in the bay

Engraving of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror departing for the Arctic in 1845

The Inuit hunter gatherers who eked out living in Canada’s arctic north shared stories about occasional encounters with “Kob-lu-na”, their name for European explorers who ventured into their brutally harsh homelands. But no tale was more dramatic than that of the two massive umiaks, loaded of scores of sailors, that became icebound as winter set in on their favored seal-hunting grounds.

These outsized boats were the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, which set out from Woolwich, England, in the spring of 1845, intent on finding a northwest passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans over Canada’s Northern Territories. Early in Queen Victoria’s reign, Britain was pressing to expand its command of the seas and the lands they touched. Finding a shortcut from England to its developing territories in the Pacific could ease trade, and bring glory and wealth to the kingdom. Polar voyages also yielded data on the differences between magnetic north readings and true north on ship charts, important for computing navigational courses.

Both ships were old, but exceedingly well adapted for the rigorous expedition. The Erebus was built at the Royal Navy at Pembroke Dockyard in Wales in 1836. The Terror was built at Topsham, Devon, in 1813. Both were bomb vessels, built to withstand the recoil from firing mortars, and with reinforced hulls to weather the impact of cannon fire. The Terror had been involved in several battles, including some against the United States in the War of 1812. After being retired from military use, the ships were further outfitted for Arctic and Antarctic exploration. Their shallow drafts were ideal for pushing through icy waters. Heating systems were added for comfort in officer and crew quarters.

Sir John Franklin

Preparations for the exploration extended beyond physical alterations to the ships. Crews would need food and other provisions to endure an epic expedition, including enough canned soups and meats to feed 130 seamen for three years. Grains and livestock were gathered aboard the vessels along with 2,700 pounds of candles and 7,000 pounds of tobacco. One item was deliberately left off the packing list – alcohol – to lessen chances of minor spats turning into drunken brawls.

Commander James Fitzjames

Sir John Franklin was selected to lead the expedition from the Erebus, which was captained by James Fitzjames, a rising young officer. Francis Rawdon Crozier was named as second in command and helmed the Terror. Both Franklin and Crozier had served on Antarctic explorations led by Ross between 1839 and 1843, during which Crozier captained the Terror. Franklin also had Arctic experience as second in command of an 1818 expedition toward the North Pole on the ships Dorothea and Trent. And he led two overland explorations of the Arctic coast from 1819 to 1822 and 1825 to 1827. From these and other northern explorations, it was thought that a passage to the Pacific might be found through Lancaster Sound, which had been blocked by Ice in earlier voyages. Piecing together data from earlier expeditions, the trans-oceanic passage was estimated to be about 1,040 miles.

Captain Francis Crozier

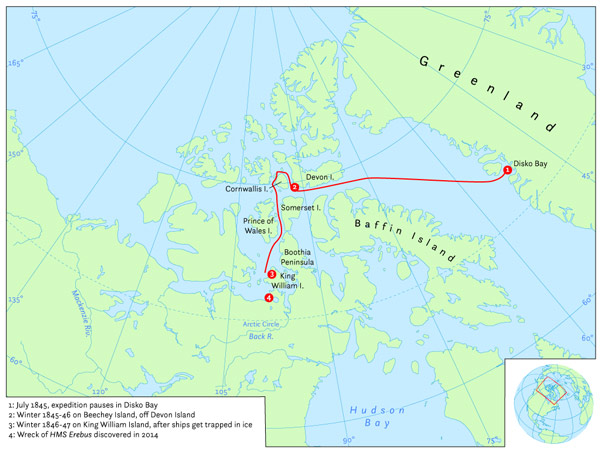

On May 12, 1845, the last of the provisions were packed onto the ships, and the 139 seamen selected for the adventure turned pay advances over to their families. In addition to cattle for food, the crew brought a cat and a Newfoundland dog named Neptune. Franklin’s wife Jane gifted the captain with a monkey named Jacko to entertain him on what was expected to be a journey lasting for years. The ships made their way first to Stromness, the port on Orkney Island, to replenish water and replace cattle that had been killed in a storm. They then proceeded to Disko Island, Greenland, where five crewmen who had fallen ill with tuberculosis were put ashore.

They were the lucky ones.

Lady Jane Franklin, John Franklin’s wife

Early July saw a melting of ice, so the explorers departed Greenland. Sailors on whaling vessels were the last to see the ships as they sailed into Lancaster Sound, heading westward to Beechey Island, where they elected to wait out the oncoming winter. Three men who succumbed to the rigors of the journey were buried on the island. Crewmen passed the time dining off packed provisions until April 8, 1846, when ice cleared to allow passage on Peel Sound. Their travels were blocked by ice off King William Island on September 12, so the brave souls hunkered down again to weather another winter. Their spirits still seemed upbeat through the winter, with a crewman Harry Peglar penning an uplifting song in his diary in April. Yet the ships remained icebound. In May, a six-man party left the ships to head overland to cairns at both Victory Point and Gore Point, where Ross had piled up the rock monuments on an 1831 expedition. At both they left notes written by Fitzjames saying that all were well.

Optimism faded as the ice block failed to clear during the summer of 1846 and the ships remained icebound throughout 1847. The Terror crew shifted to lodging on the Erebus to consolidate their provisions on the vessel most likely to become free of ice. By 1848, hopes dimmed even further, and another party traveled overland to the Victory Point cairn to add notes in the margin of their earlier message saying both ships remained icebound and that 24 men had died including Captain Franklin and eight other officers.

Although the second note said the ships were being abandoned with a goal of walking some 100 miles overland to a Canadian outpost at Back River, Hudson Bay, many survivors stayed behind, hunkering down on the Erebus. Enough ice melted by spring 1849 to release the ship. They quickly mounted the sails to head out in July only to become icebound again in August off Imnaguyaaluk Island, on a peninsula where the Inuits later told of crewmen with guns and their trusty Newfoundland Neptune joining them in a hunt for caribou. Reports of additional contact with survivors were passed down orally among the natives. Some of them boarded the ship in the dead of winter to see gaunt crewmen watching mutely as the Inuits scavenged the vessel for lumber and metals. Remaining men split into smaller groups heading south in hopes of making it to Hudson Bay. One native tale held that a crewman took up with an Inuit woman and stayed behind with his adopted family. So maybe another of the ill-fated crew got lucky after all.

The overdue expedition raised alarms in England, and more than 30 searches were mounted by land and sea to determine its fate. After England abandoned its search, Lady Franklin funded seven additional expeditions to search for the hapless crews. No survivors were found, but search parties did turn up evidence of them, including skeletal remains, burial sites, personal items and stories from Inuits about the lost Kob-lu-na.

Man Proposes, God Disposes by Edwin Landseer

Efforts to find the men and their ships fascinated the Victorian public, inspiring plays, artworks and ballads like “Lady Franklin’s Lament” about the loss of her husband. During an 1854 survey of the Boothia Bay Peninsula, John Rae heard from the Inuit of cannibalism among 35 to 40 survivors who tried to forestall starvation. He collaborated these stories with evidence of body parts in cooking pots and bones bearing markings from cutting off flesh. His discovery touched off horror among English society that nearly ruined his career as an explorer. Even author Charles Dickens weighed in on this universal disbelief that British gentlemen would consider resorting to such base behavior. Surely the savage natives were to blame for consumption of human flesh.

Some recovered bones were later found to have an elevated lead content – likely from solder contaminating the canned goods – which may have contributed to their demise. There also was evidence of scurvy, diseases and starvation. One crewman’s remains were found near a trove of books, suggesting he preferred to face inevitable death with a good read than pack food that could have prolonged his life.

While natives’ tales were dismissed in their day, it was the Inuit who cracked the mystery of the ships and their crews. Their oral history had been ignored by Europeans for generations. But by the early 21st century, researchers began to believe them.

Side-scan sonar images of Erebus

In September 2014, Parks Canada staffer Ryan Harris, acting on a map hand-drawn by Inuit descendents, searched waters off King William Island, locally called Ugjulik, that had been tagged as the site of one of the wrecks based on ancestoral lore. There he saw the shadow of a ship, which turned out to be the Erebus. Then in 2016, Sammy Kogvik, a local resident, provided information that led to the discovery of the Terror, sunk about 45 miles away at a depth of about 75 feet in what cartographers named Terror Bay. Since then, Parks Canada reached agreements with the Inuit Heritage Trust and Kitikmeot Inuit Association to gather information and preserve the sites of the ill-fated expedition.

As global warming heightens storms over the wreck sites, the agencies are combining their energies to document the wrecks, with archeological divers visiting them to collect artifacts for preservation and display at the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site at Uqsuqtuuq on King William Island.

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Fascinating! What a story!

Almost as we read in the book “Arctic drift”. Awesome to read the original stories of what these sailors had to go through