The Curse of the Mary Celeste

Mary Celeste, then named the Amazon, enters Marseille harbor in 1861. Artist unknown. Wikipedia.

What became of the crew is a mystery that has piqued the world’s top storytellers. Not long after the ghost ship was found, Cornbill Magazine ran a riff on the facts. The anonymously written article, “J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement”, laid the fate of the misspelled “Marie” Celeste to former slaves seeking vengeance for the cruelty suffered at the hands of their white American owners. When readers marveled that surely the father of the modern detective story – Edgar Allan Poe – must have returned reincarnate, the article’s author quit his day job as a ship’s physician to begin writing full time using his full name, Arthur Conan Doyle.

Other fact-challenged accounts from alleged survivors circulated in The Strand Magazine, the New York Herald Tribune and the London Daily Express. All were exciting reads, but none provided their authors with the professional lift enjoyed by Doyle, who was eventually knighted for his contribution of Sherlock Holmes and other characters to Victorian Literature. The Mary Celeste story inspired radio and stage plays into the 1930s, when the British movie house Hammer Film Productions released “The Phantom Ship” starring top-billed horror actor Bela Lugosi as a deranged sailor behind a murder mystery.

Rochelois Bank reef, the lighter area between Gonave Island and the Haiti mainland, is the final resting spot of the Mary Celeste. Wikipedia.

Storytellers ascribed the disappearance of the crew to pirates or thieves, though that was unlikely as the ship was found with all its cargo and personal belongings intact. Others suggested some sea monster had attacked the ship, though it showed no signs of an epic struggle. Some science fiction buffs suspected abduction by space aliens while spiritualists posed witchcraft or mass hallucination led to the abandonment. Likely, only Poseidon will ever know the true fate of those aboard the ship that was initially christened the Amazon when it launched from Joshua Dewis’s shipyard into the Bay of Fundy, Nova Scotia, on May 18, 1861.

The Amazon was a brigantine, a two-masted ship built with flush, rather than overlapping hull planking, creating a more streamlined caravel design. The ship was 99.3 feet long, 25.5 feet wide and 11.7 feet deep, with a gross weight of 198.42 tons. Dewis selected one of his business partners, Robert McLellan, as captain, and he set out in early June to pick up a load of lumber at Five Islands, Nova Scotia, for transport to London, England. McLellan oversaw the loading, but fell ill as the ship departed, so it returned to Spencer’s Island, where, perhaps ominously, this ship’s first captain died on June 19. John Nutting Parker took over the helm to resume the trip to London, having more misadventures along the way. It snagged on fishing equipment in the narrows off Eastport, Maine, then collided with and sank a brig in the English Channel. Upon returning to America, the Amazon uneventfully transported goods to and from the West Indies, England and the Mediterranean until October 1867 when a storm slammed it ashore at Cape Breton Island off Nova Scotia.

The badly damaged hulk was salvaged by Alexander McBean, of Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. He sold it to Richard Haines, an American mariner, who had it patched up and renamed the ship the Mary Celeste, believing in the superstition of renaming a ship would change its luck – hoping in this case for the good. He then named himself captain and had it towed to New York. There is no record of the newly renamed ship hauling any cargo as its owners shifted over three years until October 1869, when it was finally seized by Haines’ creditors. Under the new owners, the ship underwent a major refitting, lengthening it by three feet and deepening it by three feet. A second deck was added, and the poop deck was extended. The transoms and many hull timbers were replaced, bringing the ship to 282.28 tons.

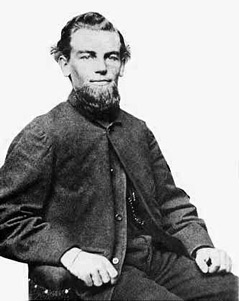

Mary Celeste Captain Benjamin Spooner Briggs. Wikipedia

Eight days later, Captain David Morehouse left Hoboken, N.J., on the Canadian brigantine Dei Gratia with a load of petroleum, also bound for Genoa. Midway between the Azores and Portugal on December 4, he espied a poorly trimmed ship with erratic movements, leading him to believe something was amiss. He dispatched a crew on a skiff to board the vessel emblazoned with the name Mary Celeste on its stern. They found no sign of life. The main hatch was secure, but fore and aft hatches were open with covers beside them on the deck along with a partially dismantled pump and a sounding rod to measure water in the hold. The ship’s lifeboat was gone. Below deck were ample provisions, and clothes and other personal items all neatly stowed. The ship’s papers and navigational instruments were missing. However, the log was in the captain’s quarters with a final entry dated at 8 a.m., November 25, recording its last position off Santa Maria Island in the Azores, nearly 740 nautical miles southwest of where the ship was found.

Captain Briggs’s wife, Sarah, with their son, Arthur. Findagrave.com

Regardless of the scenario, the ship and its cargo were valuable, so Morehouse assigned several crew to the Mary Celeste to assist in bringing it to port at Gibraltar. Salvage hearings there could find no evidence of foul play, but awarded Morehouse and his Dei Gratia crew only one-fifth of the value of the ship and its contents, suspecting that some wrongdoing might have been involved in the abandonment. The Mary Celeste was released by the court to be sailed to Genoa by Massachusetts Captain George Blatchford to deliver what was left of its cargo. It was then sailed back to New York, arriving in September at a considerable financial loss to the shareholders.

The Mary Celeste’s reputation worsened as the new owners regularly lost money hauling cargo on West Indies and Indian Ocean routes. In February 1879, Captain Edgar Tuthill fell ill and put in to Saint Helena Island where he died, furthering the Mary Celeste’s image as a cursed ship. It passed through more owners before landing in the hands of a Boston partnership headed by Wesley Grove. The port of call and captain’s chair shifted several times until 1884 when Gilman Parker was named to head the helm.

Map shows course of Mary Celeste after leaving New York harbor. Wikipedia

Of those whose lives were touched by the curse of the Mary Celeste, one survived relatively unscathed. Captain Briggs’s son, Arthur Stanley, initially raised by his maternal grandmother became the ward of his father’s brother. He became a commercial bookkeeper for a local coal company, and married Margaret Hovey Holmes, a public school teacher. They had two sons, and their descendants still live in Plymouth County, Massachusetts.

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Always been intrigued by this ships history, like many others. I enjoyed the book Brian Hicks wrote with an excellent account of the Celeste, titled Ghost Ship, he also had commentary from Clive Cussler with excerpts from the Sea Hunters II book

Thank you. Very interesting information.

Please continue your hard work