The Flight of the Dove

Ship similar to the Dove

Life for European commoners was tough early in the nineteenth century. The Holy Roman Empire had just collapsed and political entities jockeyed to fill the power void. What’s now Germany was an amalgam of independent kingdoms, states and cities united only in a shared language and a drive to expel French control from their lands.

Parishioners in a small Lutheran church in the village of Reichenbach, near Stuttgart, groused about high taxes, even higher prices, and inflation that ate into their meager incomes as farmers and millers. Sons who should work the fields were being drafted for war efforts. And draconian laws limited their options. Former army officer Johann Adam Tracht complained he couldn’t even use his guns to hunt meat for the table on his own property. Talk of their bleak existence turned to news from America, which had just passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 forcing the relocation of indigenous people to barren lands west of the Mississippi River. What became known as the “Trail of Tears” among the natives was a welcome mat for immigrants, opening up millions of acres of bounteous forests brimming with game and farmland selling for $2 an acre. Children could be free from the military draft that pulled families apart.

The Tracht clan of 22 and the family of fellow churchman Johann Peter Arras united in a plan to head to America, drawing support of friends and neighbors. They sold off their lands and packed their valuables, especially those hunting rifles, to prepare for frontier life in a fledgling country. In May 1831, 150 brave souls set off from the Odenwald region, heading up along the Weser River valley through Darmstadt and Kassel to Breman on the North Sea. There they made arrangements to take the Brig. James Beacham Galt for passage to Baltimore.

The Beacham was a handsome new ship. It was 118 feet long, 28 feet wide and 20 feet tall. Its two masts could support 24 sails, and it could carry 7,800 tons of cargo. Passengers were instructed to pack enough food for a 32-day crossing. Eggs, cheeses, sausages, potatoes, beans, peas, barley, rice, wines and water were stowed for later days, with meats and breads to be consumed during the first two weeks. As the ship left port on August 1, the immigrants dubbed the vessel the “Dove” as a metaphor for their flight to a land of freedom.

The voyage was mostly smooth sailing – too smooth. They were becalmed for 12 days, and encountered headwinds that blew the ship backwards a few times. Two children died en route and were buried at sea. Then as they approached Baltimore on September 16 – 46 days into their voyage – a nor’easter arose with strong winds and punishingly high seas that blew them well off course to the south. The rudder broke, leaving the Dove at the mercy of nature when it slammed hard afast on a submerged sandbar. The captain ordered the masts to be chopped down to keep his vessel from being further thrashed by winds and crashing waves. Then he started herding his crew toward a lifeboat, intent on abandoning his passengers to the mercy of the seas.

Tracht would not suffer his charges to be lost to the cowardice of a captain who had been derided as a drunken sot during the journey. He fetched his seven rifles from the hold, passed them out to his family and vowed to shoot any crewmen who dared to leave the ship before every woman and child was safely on land. Little Margaret Arras recalled a story from the New Testament about Jesus calming the Sea of Galilee for his disciples, and suggested singing to God for mercy, which prompted a crewman to slap her to knock some sense into the 14-year-old’s head. She nevertheless began singing Martin Luther’s hymn, “Our Mighty Fortress is Our God”, and soon the congregants and many crewmen joined in. As their voices rose to the heavens, the tempest began to subside. When dawn rose on September 17, they were greeted with calm waters, and could see strange dark-skinned people gathering on the nearby shore.

The African slaves were the first Black people the Germans had ever seen. Just weeks before the Dove ran aground about 40 miles south of Cape Henry, Virginia, the slaves had suffered defeat in the nearby bloody Nat Turner rebellion. Yet they were the good Samaritans who helped the passengers and crew ashore. Tracht set up lines to help with the orderly transport of people and cargo, and was the last to leave as the Dove succumbed to the sea. All were so grateful that they vowed to celebrate this miraculous survival for generations to come.

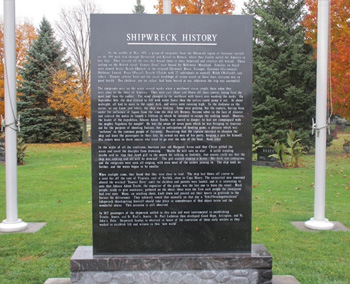

Marker near Arlington, Ohio, photo by the Rev. Ronald Irick, https://www.hmdb.org/

The survivors initially gathered near Norfolk, Va., before moving on to New York, then Baltimore. Some had lost most of their possessions and opted to work in the area to earn money to buy what would be needed for living on the frontier. The survivors agreed to assemble in northwest Ohio, an area that had been described by locals as being similar to the land they left behind in Odenwald

Over the next few years, survivors made their way to Ohio, set up new homes and established churches where they could offer prayers of thanks. They held true to their vow to remember their good fortune. To this day, September 17th is celebrated as “Schiffbruchs Gottesdienst” or Shipwreck Thanksgiving Festival at Trinity Church and Saint Paul’s in Jenera, Good Hope in Arlington and St. John’s in Dola. People can pause to remember the fateful deliverance year-round at a marker in the St. Paul Evangelical Lutheran Cemetery at the intersection of County Roads 32 and 66 near Arlington.

As a young reporter for The Courier, the newspaper that covers northwest Ohio, writing news announcements and local stories about the shipwreck festival every year aroused my curiosity about ships and perils of the sea. This led to an interest in shipwrecks and scuba diving that I pursue to this day.

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.4 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Ellsworth will be sorely missed, but Bob is a worthy successor. (Immersed Magazine was fantastic!) Looking forward to reading more of his contributions.

Wow! Great story!

Hello. A very distant relative of mine and his family were on the ship, Joh. Michael Bauer. Do you have a map showing where the ship ran aground? Thank you very much.

Joann Tracht was my 4th great grandfather. My mom, Ada was born in Middletown, Ohio in 1926 the second born daughter. Her family moved to California when she was 7 years old. Love reading the different variations and details of this great story of how our ancestors immigrated to the US.