The Muse in the Sea

Earl of Abergavenny is depicted in a painting by Thomas Luny. Portland Museum Trust.

When the Earl of Abergavenny sank in 1805 off England’s southern coast, the death toll in the hundreds made it the nation’s worst maritime disaster. The tragedy even sank the soul of a man who was not on board, yet that might have inspired him to rise to become the poet laureate of the United Kingdom.

William Wordsworth was the older brother of John Wordsworth, the captain of the Abergavenny who went down with his ship while trying to steer it to a safe grounding. The younger Wordsworth took to the sea for a stable income that could help support himself as well as provide financial assistance for his older sibling’s artistic endeavors. His death had a profound effect on William’s outlook on life, shifting his view of nature from uplifting to bleak.

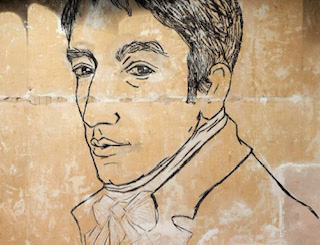

Poet William Wordsworth was the older brother of John, the ship’s captain. National Trust.

In the wake of the loss, William penned:

“A power is gone, which nothing can restore;

A deep distress hath humanized my soul.

Not for a moment could I now behold

A smiling sea, and be what I have been;

The feeling of my loss will ne’er be old.”

John was featured in William’s works following the tragedy including Stepping Westward, The Character of the Happy Warrior and the Elegiac Stanzas. The captain’s early contribution gave William financial footing to rise in literary circles, ultimately to be named by Queen Victoria as poet laureate in April 1843. He served in that capacity until his death from pleurisy on April 23, 1850.

Deadeye and other items salvaged from the ship can be seen at Portland Museum. Portland Museum Trust.

While William was known for his literary descriptions of traveling countrysides of England and France, John was more taken to seeing the world by the sea. Born the fourth of five children to John Sr. and Ann Cookson Wordsworth in the inland city of Cockermouth, John followed the River Cocker to the sea to pursue a life fostering the United Kingdom’s growing worldwide colonization. A central pillar in that expansion was carried out by the East India Company, which controlled trade in a vast swath of India, and used that base to export spices, tea and silk from throughout Southeast Asia. Big trade required lots of ships and mariners to operate them.

The Earl of Abergavenny was one of the largest East Indiaman ships built by Pitcher of Northfleet in Kent, England. It was 177 feet long over a keel of 144 feet, with a beam of 13 feet, 8 inches, and a 17-foot, 6-inch deep hold capable of hauling 1.498 metric tonnes of cargo. Three masts and a long bow sprit supported a full complement of sails. It launched December 15, 1796, primarily to supply colonists in India, and return with goods to market in England and its trading partners. It saw brief action in the Battle of Pulo Aura, a skirmish in England’s Napoleonic Wars, but did not fire any of its considerable armament of cannons. East Indiaman ships were well armed with 32-, 18-, 12- and 9-pound cannons to discourage pirates, and were often accompanied with British Navy ships through politically sensitive waters.

John Wordsworth took over as captain of the Abergavenny from his uncle of the same name, who piloted the ship on its first two voyages around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope where the Atlantic gives way to the Indian Ocean. The meeting of the warm-water Agulas current with the cold-water Benguela current is known for its treacherous seas that test the mettle of captains and their crews.

Map of Weymouth Coast shows wreck site. Metro.co.uk.

John Junior captained the Abergavenny’s third successful trip to India in 1801 to 1802, which was uneventful. War broke out during its fourth trip in 1803 to 1804, when, along with a small fleet of East Indiaman merchant ships, it encountered a French naval squadron. Although outnumbered and with less firepower, the convoy of trade ships outmaneuvered the French warships to scare them off before continuing on its journey.

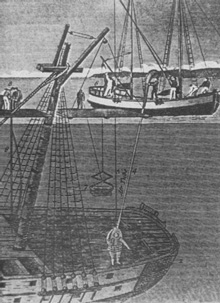

Sketch of John Braithwaite using a Tonkins dive machine to salvage the Earl of Avergavenny. Researchgate.net.

Wordsworth began the Abergavenny’s fifth trip to India in fair sailing weather, setting out from Portsmouth on February 1, 1805, with four other East Indiaman ships and a navy escort vessel. On February 5, a storm churned calm seas into angry whitecaps that shoved the ship on to the Shambles rocks off the Isle of Portland in Weymouth Bay. He pointed the bow toward the nearest beach, but the ship was too damaged to make it. Of the 402 persons aboard, 263 perished, including the captain, who later was blamed along with the stormy weather for the wreck. Beyond the tragic loss of life, the vessel sank with 30 casks of wine and, of most interest to the British Empire, 62 chests of silver, worth about $10 million in today’s dollars.

John Wordsworth’s cuff links. Portland Museum Trust.

Barely had the ship settled 60 feet to the bottom when efforts to recover the precious metal got under way. John Braithwaite had a record of successfully salvaging cannons and cargo from other wrecks, and was pressed into service by the British admiralty to recover at least the silver from the Avergavenny. He opted for a diving machine designed by a Mr. Tonkins. It consisted of a body of copper, iron boots with joints of chainmail, leather covering the joints to protect from being cut, arms of strong leather and a helmet outfitted with a 1-inch-thick glass faceplate about the diameter of a dessert dish. The suit was further strapped with lead weights and attached to a heavy rope to raise and lower the diver, who received air pumped by a bellows through a leather hose.

John Wordsworth is interred at Portland. Findagrave.com

Using the primitive surface-supplied diving gear, Braithwaite managed to savage much of the wreck’s contents, sometimes directing a saw on a long handle operated by surface crews, and placing dynamite charges to move the ship’s big timbers. All 62 silver chests were hauled to the surface, as well as lesser items, including cufflinks believed to have been worn by Captain Wordsworth. Many of the salvaged items can be seen at the Portland Museum near the wreck site. Among its collection are ship fittings that were revolutionary in their day, such as iron knees that were used to strengthen joints on large wooden ships.

The wreck site recently gained protected status, so adventurous historians and English literature buffs don’t need any special permit to see the Avergavenny on scuba today, so long as they take only pictures and leave only bubbles. Hull planks and frame ribs protrude from the muddy bottom, with various fittings scattered in an area about 150 by 30 feet. Expect to find bracing conditions of low visibility and moderate currents. Bottom temperatures can dip to 43 degrees Fahrenheit depending on the season, a chilling reminder of those who lost their lives in the stormy, icy seas some 200 years ago.

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

0 Comments