A Pacific Passenger’s Apprehension

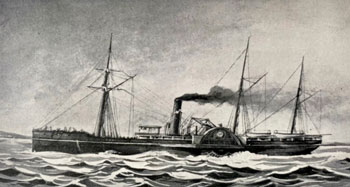

Woodcut depicts the S.S. Pacific under way. Public domain.

Fanny Palmer felt uneasy as she headed to Victoria, British Columbia’s Esquimalt Harbor on the morning of November 4, 1875. The 18-year-old daughter of a local college professor was going to board the S.S. Pacific for one of its bimonthly runs to San Francisco.

“I feel like I’ll never see you again in this world,” she told friends as she packed to visit her brother.

Her words could not have been more prescient. The side paddle wheel steamship was about to sail into history as the worst maritime disaster in the Pacific Northwest of that era, taking hundreds of passengers to their deaths along with a cargo of gold worth about $1 billion today.

Fanny Palmer. MyNorthwest.com.

Fanny’s mother shared a similar vibe as she sobbed, watching the steamer’s smoke trail dissipate above the sea.

“I’m seeing the last of Fanny,” she told David W. Higgins, editor of the British Colonist, a Victoria newspaper.

Higgins had just been aboard the Pacific chatting with business associates as it prepared to embark on a routine trip as the gold mining season was winding down with the approaching winter. As he left for the dock, a rush of new passengers filled the ship with at least 500 people he estimated, although others put the passenger figure at about 300. Its lifeboats were rated for 160. Carpenters were called in to hastily build more bunks for the last-minute crowd. While improvised accommodations were being installed, stevedores busily packed the hold with 200 pounds of gold, 300 bales of hops, 2,000 sacks of oats, 250 hides, 11 casks of furs, 31 barrels of cranberries, two cases of opium, six horses, two buggies, 280 tons of Puget Sound coal and about 30 tons of miscellaneous goods. The ship finally pushed off nearly an hour late at 10 a.m. with a bit of a list. At the wheel was Jefferson Davis Howell. The seasoned captain was a Civil War veteran named for his much older brother-in-law, Jefferson Davis, who rose to become the Confederate President.

Captain Jefferson Davis Howell. Wikitree.com.

In 25 years of service, the Pacific had built a reputation for reliable service. The steamship was commissioned by Major Albert Lowery and Captain Nathanial Jarvis, and built at William Brown’s shipyard at 12th Street on New York City’s East River. It was 233 feet long with a 33.5-foot beam, capable of hauling 876 tons with a passenger capacity of 546 plus a crew of 52. Two coal-fired boilers powered its 275-horsepower steam engine with a 72-inch cylinder and a 10-foot stroke that spun side paddle wheels to achieve a top speed of 16 knots or about 18 miles per hour.

The Launch

A gala aboard the Pacific the day after its September 24, 1850, launch featured a race down the East River in which it handily passed competitors including the Cunard line’s newest steamer, the Asia. Captain Jarvis was at the helm and invited passengers included Gen. Jose Antonio Paez, the exiled Venezuelan president, shipbuilder William Brown and several other steamship captains.

After the festivities, the Pacific settled into regular service in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico with runs between Havana, Cuba, Chagres, Panama, and New Orleans, carrying passengers, cargo and mail. Then owner Cornelius Vanderbilt decided to take advantage of the blossoming California gold rush and shift the Pacific to serve the ocean for which it was named. On March 18, 1851, it sailed south to pass from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans to begin a new service between San Francisco and Juan del Sur, Nicaragua, where passengers and cargo could be shuttled overland to Atlantic waters in travel before the Panama Canal was built. After ironing out deals with the government, the Pacific maintained regular service to Nicaragua until 1855 when Vanderbilt’s properties there were seized in the country’s civil war.

Coal came from the mine that fueled the S.S. Pacific.

The ship fell out of service until 1858 when the discovery of gold in British Columbia’s Fraser Canyon shifted the western gold rush north of San Francisco. The Pacific Mail Steamship Company acquired the Pacific for runs between San Francisco, Portland, Puget Sound and Victoria. Besides passengers, it hauled mostly agricultural goods until July 17, 1861, when it hit the aptly named Coffin Rock in the Columbia River at 2 a.m., sailing out of Portland, Oregon, bound for San Francisco. Flooding was severe, but Captain George W. Staples managed to get the ship 10 miles downstream before beaching it on the Washington side of the river. After being refloated and repaired, it was back in service along the West Coast. With the acquisition of Alaska from Russia, the Pacific expanded its runs to the territory, hauling ordnance and commissary supplies to stock new military posts. The new owner, the North Pacific Transportation Company, even extended the routes as far west as Honolulu as shippers looked for new ways to make money in the highly competitive shipping market.

Steady use and being constantly marinated in seawater was taking a toll on the Pacific by 1873, when it underwent a refit in August on its routine stop in San Francisco. A new steam engine was installed boosting propulsion to 500 horsepower. Carpenters examined the ship for deteriorating wood, but some say they just slathered on thick coats of paint rather than replace aging hull timbers, so everything looked shipshape above the waterline. After a merger, the ship’s ownership shifted to the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, and the Pacific returned to plying its old route between San Francisco and Victoria.

Not So Routine

The Pacific seemed a bit akilter as it steamed out of port and down the Strait of Juan de Fuca on its final trip. Henry F. Jelly, a civil engineer for the Canadian-Pacific Railway who was a passenger, noticed the ship tilting to starboard. And workers on a dredge it passed observed that its steering was so erratic that something must have been wrong. To correct the list, crews filled the port-side lifeboats with water. Then later when the tilt shifted abeam, they drained the lifeboats and pumped water into those on the starboard side. Passengers began being jostled by rough seas as they headed past Tatoosh Island at about 4 p.m. when the ship turned south, heading directly into oncoming wind and sizeable ocean waves.

Cape Flattery Lighthouse. Alslighthouses.blogspot.com.

Around 10 p.m., Jelly was jolted in his berth and went up on deck where the crew told him there’d been an accident, but there was no problem. Thus reassured, he retired again to his cabin.

The Pacific had struck the bow of the Orpheus, a 1,100-ton square-rigged sailing vessel traveling north along the Washington coast en route to pick up a load of coal at Nanaimo, British Columbia. Apparently its crew mistook the Pacific’s lights for the Cape Flattery Lighthouse and turned into its path. Orpheus Captain Charles Sawyer quickly inspected his ship, which had nominal damage above the waterline. He saw no sign of the Pacific after the collision, so he assumed it also was relatively unscathed. The Orpheus continued on its journey, but Nemesis wreaked revenge for leaving the scene of the accident. Its crew later mistook another lighthouse beacon and turned into a rocky shoal near Copper Island, sinking to the west of Vancouver Island. But that’s material for another Shipwreck Logbook entry.

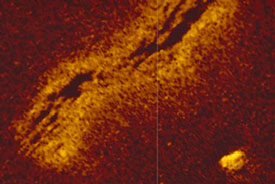

Sonar scan of wreckage believed to be the S.S. Pacific. Northwest Shipwreck Alliance.

The Orpheus crew was derided for not assisting imperiled Pacific passengers, but they said it was because the event unfolded so quickly. “When, after I found I was not seriously damaged,” Sawyer later testified. “I looked for the steamer. I just saw a light on our starboard quarter, and when I looked again, it was gone.”

As the Orpheus sailed on, pandemonium gripped the Pacific. Jelly and Neil Henly, the ship’s quartermaster, were jostled from their bunks by another bump and heard the sound of rushing water as they darted topside. Passengers were scrambling for the four lifeboats, many without oars and still holding water from the earlier attempts to correct the ship’s shifting list. Jelly looked for distress signals only to find the pilot house empty with no one at the wheel as the ship steered wildly with the engine still running. He made his way to one of lifeboats, which were all stubbornly stuck in place and could not be lowered. Boarding one, he saw passenger Jennie Parsons, weeping while clutching her 18-month-old son who had been crushed to death by a man falling on him in the mayhem. He also helped a girl onto the boat who fit the description of Fanny Palmer.

Fanny Palmer’s grave. MyNorthwest.com.

As the ship quickly sank, frozen pulleys became a moot issue for lowering the lifeboats. Yet no sooner did the boats hit the surface, when they overturned, throwing Jelly and his fellow passengers into the frigid water. Women burdened with heavy clothing of the day sank immediately as the men clung to the overturned lifeboat, watching the Pacific roll on its side, break in half and sink. The 150 or so people on the deck howled as survivors reached for any flotsam they could grab. As wailing of the doomed died down, Jelly clung to a piece of the wheelhouse and floated for a day and a half before being plucked from the water by the Bark Messenger after dawn on November 6. Quartermaster Henly joined ship’s captain, second mate, cook and four passengers on a fragment of the ship’s deck. As hours passed the men succumbed to hypothermia, passing one by one until only Henly remained. He was picked up November 8, 80 hours after the wreck, by the revenue cutter Oliver Wolcott. Only Jelly and Henly survived.

On November 25, Victoria police were called to investigate a body that had washed up near the United States Garrison on San Juan Island. It was a female with light brown hair of medium size, clad in a nightdress, waterproof cloak, striped hose, unlaced No. 3 kid boots and entangled in a life preserver emblazoned with S.S. Pacific. After 21 days at sea, Fanny Palmer’s body had retraced the nearly 100 miles back to land, coming to rest almost within sight of her home.

Read More: Discovering the S.S. Pacific

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

0 Comments