U-1206 Flush Ends Wartime Gamble

U-1206 at dock. WikiMedia commons.

Even the non-poker players on the U-1206 had a sense they survived World War II because of a flush.

In the latter days of the war, being assigned to crew a German U-boat amounted to a death sentence. Some 75 percent of U-boats were documented as sunk or listed as missing in action. The boats were assigned to lanes most likely to be used by Allied ships that were heavily guarded by cruisers laden with depth charges, and airplanes ready to bomb any U-boat that neared the surface. Mines were strategically deployed along lanes to explode at the slightest brush of a submarine hull. Highly developed sonar could sense U-boat movements underwater, bringing barrages of depth charges from patrol boats.

A German U-boat under attack by navy bomber.

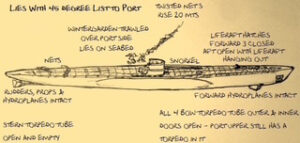

U-boats could lie undetected on the seafloor for only so long before they had to surface to replenish their air supplies, recharge their batteries and empty the septic tanks. The latter task could take on a high level of urgency, with about 50 crewmen on board eating and drinking, which, of course, lead to the need for going to the bathroom. By 1943, German engineers designed a compressed air system that could jettison the waste at depth, thus freeing up space that had been used for the large septic tank. The system was tricky to operate, so crews had to receive special training to avoid causing the seawater and waste to back up into the vessel.

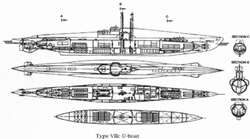

Construction on the U-1206 began on June 12, 1943, at the F. Schichau Gmbh yard at Danzig. The Type VIIC sub had all the latest innovations, including the wastewater ejection system. At 220 feet, seven inches long, with a beam of 20 feet, four inches and a height of 31 feet, six inches, the U-boat was well designed for its mission of sinking ships. Four bow tubes and one rear tube could rotate through the 14 torpedoes on board. It also carried 26 mines to deploy in shipping lanes. Four antiaircraft guns were mounted topside for defense on the surface. Its pressurized hull could withstand a dive to 750 feet. Twin diesel engines could propel it at 17.7 knots topside for up to 9,800 miles. Underwater, electric motors could power it at 7.5 knots for 92 miles.

Diagram shows deck plans of a German VIIc U-boat. Wikipedia.

After being launched December 30, 1943, the boat underwent field tests and crew training exercises until July 1944, when it was assigned to Kapitanleutenant Karl-Adolf Schlitt, a 27-year-old from Kiel, Germany. The boat underwent further improvements with the installation of a Schnorchel underwater breathing apparatus and the painting of its distinctive emblem of a white stork on a black shield before being released for patrol duties. On April 2, 1945, crewmen filed what they feared would be their last letters to wives and girlfriends before the sub headed out of Horten Navel Base, then on to Kristinsand to prey upon Allied ships In the North Sea.

On April 14, the U-1206 eased into a calm spot 8 nautical miles off Peterhead, Scotland, where it hovered at about a 200-foot depth while engineers tuned its twin diesel engines. Kapitan Schlitt took advantage of this down time to go to the head, according to several accounts of the day. After answering the call of nature, he became uncertain of the proper procedure to flush the cantankerous commode, and summoned an engineer more familiar with the toilet. After hearing Schlitt’s description of his efforts thus far, the engineer confidently turned a valve only to be blasted with a geyser of sewage and seawater propelled into the tiny toilet space by seven atmospheres of outside pressure.

Kapitanleutenant Karl-Adolf Schlitt. Uboat.net.

Schlitt’s and the engineer’s strongest efforts could not slow the blast, soaking them and flooding the compartment with water, which then seeped into the sub’s battery bank, a deck below. Saltwater reacted with the battery acid and began filling the sub with toxic chlorine gas. Schlitt had no choice but to get the sub to the surface before it became the coffin for him and his crew. Schlitt summoned the remaining battery power to empty ballast tanks and fire torpedoes to jettison as much weight as possible, assuming anything of sensitive intelligence – including the design of the new toilet – would sink to the bottom, safe from Allied hands.

Dive site map made by Buchan dive team. Buchandivers.com.

Once topside, the U-1206 was quickly spotted by Royal Air Force planes, which peppered the water with bombs to seal the vessel’s fate beneath the waves. Crew scrambled to inflatable rubber dinghies. Around midnight, two Royal Navy Trawlers, the HMT Nodzu and HMT Ligny, approached the site to witness the U-1206 roll over and sink. The Nodzu crew rescued 23 men from two rafts and took them to Aberdeen, where they were taken into custody. The Reaper, a lobster boat out of Peterhead skippered by Alec John Stephen, plucked another 14 men from a dinghy and brought them to authorities for holding. A third raft with six men washed ashore some 10 miles away in an area locally known as Guite, a sandy shore at the base of a cliff south of Boddam. Survivors somehow scaled the 200 feet of rock face to be spotted by Sandy Bain, a local lad who sprinted two miles to a shop in Tillymaud, which had the nearest telephone where he could report the men to authorities.

Torpedo remains in upper forward tube of U-1206 wreck. Buchandovers.com.

Three of the men perished during the climb, and the remaining souls pondered their potential fate as they approached the Whiteshin farmhouse, near Cruden Bay. Sentiment toward Germans and their war effort was pure anger as villagers and rural residents bemoaned the death and destruction of their land and people from carpet bombing. Nevertheless, wet and chilled with hypothermia, they knocked on the door hoping for the best.

Kapitan Schlitt, left back to camera, addresses crew from the conning tower. Buchandivers.com.

Mary Pratt, the resident farmer, took one look at the bedraggled lads, shivering with cold and fear before her, and asked, “Would you like to come in for a cup of tea?” With the ice broken literally and figuratively, they filed in and offered the Pratts their treasured rations of emergency chocolate bars as Mary poured them tea in her finest china settings. Her generosity toward the German survivors was highlighted in local historian Mike Shepherd’s book “North Sea Heroes”.

Buchan divers beam after finding U-1206, ending a 12-year search for the wreck. Buchandivers.com

Intrepid scuba divers searched for the wreck for years, using charts from a seabed survey by British Petroleum for a possible line to an oilfield being planned in the North Sea. They found it in 2012 and conducted a series of technically difficult dives to 230 feet, taking underwater photos of the nearly intact wreck. A white stork on a black shield emblem confirmed the sub’s identity. Its conning tower and periscope lie nearby shrouded with netting from a fishing trawler. All but one of the torpedo tubes had been emptied in the desperate drive to surface.

Kapitan Schlitt, left, thanks a crewman, center, and skipper Alec John of the Reaper. Buchandivers.com.

Kapitan Schlitt and surviving crew spent the remaining few weeks of the war in a prison camp before being returned to Germany at its end. Schlitt became a district administrator for Oldensburg, a region in Holstein. He outlived all his surviving crew, dying at the age of 90 on April 7, 2009. He affably praised his crewmen throughout his life, and returned to Scotland in 1987 to personally thank their rescuers and visit the graves of crewmen who died in the sinking. However, he learned there that they had been reinterred in their homeland.

Mary Pratt welcomed shivering survivors with a cup of tea. Pressandjournal.co.uk.

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.3 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Here’s another amazing story! What a tale to tell the kids…

Good article! Thank you!

I found this story by following an internet rabbit hole. Reading about a diving game for the PlayStation from the 90’s, to a war story for the ages. What an incredible read, so thankful they survived to tell this tale.