Fate of the Brave Ship Sterling

A typical brigantine like the Sterling is under way at a tall ship parade. Www.pinterest.com

The Brigantine Sterling was the little ship that could and did. Yet the reward for safely sailing thousands of miles over many months to safely bring its crew and cargo to their destination was to be cast aside like a red Solo cup after a college keg party. However, the discovery of its remains reminded the Central Valley city of Sacramento of its birth as a port city during the California Gold Rush of 1849.

Compared with most ocean-going vessels of the day, the Sterling was a tiny brigantine. Samuel A. Fraser built the ship in 1833 in Duxbury, Massachusetts, with a length of just 88 feet, capable of carrying 201 tons. With a shallow draft of 11.5 feet, the Sterling could serve local ports between Boston and Philadelphia. Captain Edmund K. Gallop was content sailing between these regional markets until December 5, 1848, when President James K. Polk confirmed rumors of the discovery of gold in California during his State of the Union address. Captain Gallop envisioned making a good profit and a new life by hauling a load of cargo to the land of gold.

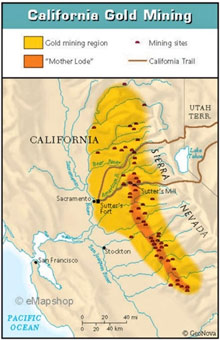

Map shows course taken to arrive at Sancramento. Copyright eMap shop.

Within a month after Polk’s announcement, Gallop packed the Sterling’s hold with merchandise to sell to the horde of ‘49ers surging toward the West Coast with visions of striking it rich. On January 3, he cast off from Beverly, Massachusetts, with seven aboard intent upon sailing down the East Coast, around Cape Horn at the bottom of South America, then up the West Coast to San Francisco. Although seemingly rushed, the departure timing was ideal for making the passage during the Southern Hemisphere’s summer season, when seas there are calmer and temperatures more moderate.

Nothing remains of the log Captain Gallop kept, but the 17,000-mile journey from New England to San Francisco was fraught with peril. Every sort of climate was faced heading south from the North Atlantic’s bitter blasts, calms in the Tropic of Cancer to torrid zones and uncertain breezes in Capricorn to frigid violent Antarctic storms near the Cape. No matter how many provisions were packed, crews would need to barter in various languages for fresh water and staples along the way. Popular stops were Rio de Janeiro, Santa Catharina Island, Juan Fernande Island, Valparaiso and Callao.

Magellan Strait is a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Wikipedia

But one more hazard remained in the approach to the Sterling’s destination.

At the entrance to San Francisco Bay lie enough shipwrecks to fill this column with stories for years. The arms of the Golden Gate embrace the 400-square-mile San Francisco Bay, leaving only a one-mile gap through which rushing tides flood and ebb. Complicating entry through this tidal flow are the region’s dense fogs that can block all view of the environs until it’s too late to avoid crashing ashore or into other befogged vessels. The Gulf of Farallones National Marine Sanctuary estimates that there are many more than the over 300 known shipwrecks on the ocean floor around the Golden Gate.

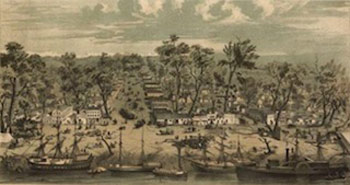

Ships line Sacramento’s old waterfront. Oldsacramemto.com

The Sterling survived that treacherous entrance to glide northeastward through the bay, then San Pablo Bay to enter the Sacramento River. Its shallow draft was ideal for the last leg of its journey, arriving at the “River City” just 180 days after setting sail from Massachusetts. It joined a growing fleet of ‘49ers ships that were becoming a floating waterfront market. Captain Gallop tied up to Sacramento’s levee, peddled his cargo, and then put his ship with all its sails and rigging up for sale. Months passed with no offers. It served as a floating store until the fall of 1855, when it sank at its mooring. Efforts to refloat it failed, as did several attempts to salvage pieces of the brig. Once city officials gave up on removing the Sterling, the Sacramento Democratic State Journal newspaper ran a fitting elegy in its November 1, 1855, edition:

Though other ships may come and other Bards may sing,

Strange Manners oft Transpire. Here’s health to thee Sterling

Here’s a hand for those who love thee.

Here’s a smile for those who hate.

A sigh for those who don’t deplore

Thy twisted watery fate.

Great scarcity of items may make reporters sulk.

But when we have our columns full

We’ll drink to thee, “old hulk.”

Site sketch is from Jack Hunter’s and John Foster’s underwater survey. Parks.ca.gov

Generations of journalists later, local reporters once again started filing stories about the Sterling in the summer of 1984 when Sacramento began an archeological survey of its waterfront as part of a project to rebuild its historic wharf. Jack Hunter investigated 18 anomalies identified by side-scan sonar. All appeared to be tree stumps or other insignificant pieces of debris except for Object 16. It turned out to be the bow section of the Sterling protruding from the mud at about 30 feet of depth.

Side-scan sonar shows Object 16, the Sterling wreck. Parks.ca.gov

Scuba divers found 44 feet of the starboard side exposed with the remaining section covered in riprap. The hull is covered with copper sheets still protecting the wood from marine organisms. An anchor chain extends from the hawse pipe, indicating it was at anchor upon sinking. Part of the upper deck is exposed, showing the stub of a mast. The hull section arches up enough to be penetrated by divers, and various metal objects protrude from a debris field that may offer insights to life in the Gold Rush. Lying parallel to the wreck is the burned hull of a flat-bottomed river craft that might have been a victim of the great Broderick fire of 1932 that devastated the waterfront and led to the construction of more permanent buildings at the site, which is just a few blocks from California’s State House.

Marine archeologists lift an anchor from the Sterling. Parks.ca.gov

The discovery is prompting Sacramento to weigh how to use the wreck to explore and preserve an artifact from a key era of the city. Sacramento started as little more than an enclave of houses and businesses called Sutter’s Embarcadero that sprung up around Sutter’s Fort at the confluence of the Sacramento and American rivers. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill at nearby Colonia, California, in 1848 brought thousands of fortune seekers to a growing city that came to be named Sacramento. The Sterling is one of only a few Gold Rush ships to be found. Beyond salvaging and displaying artifacts from the wreck, the city is considering ways to use the wreck site to call attention to the city’s history. Among the more ambitious ideas to be floated is building a coffer dam around its remains that would allow waterfront visitors to peer into the water for a glimpse of American history.

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

0 Comments