The Bad Ship Whydah Gally

A finely made model depicts the Whydah Gally. Www.handcraftedmodelships.com

Designed as a slave ship, the Whydah Gally was built to be bad. Then forcefully repurposed as a pirate vessel, it became arguably even worse. Yet in its mercifully short time at sea, seeds of democracy were sown among its crew.

Sir Humphrey Morice, a member of the British parliament and leading London merchant in the slave trade, commissioned the ship’s construction in 1715. Its name was an Anglicized version of Ouidah, the port city of Dahomey, a kingdom on the western African coast that’s now the Republic of Benin. Dahomey’s King Agaja had organized a large army that pushed deep into Africa capturing millions of prisoners to make his land the world’s leading exporter of slaves through its the Royal African Company.

British ships laden with goods would start the slave-trade triangle by sailing south, selling the wares as they’d go, then use the profits to fill now empty holds with human cargo in Africa. From there, they’d head west to Caribbean islands, where slaves were in constant demand for backbreaking hot labor in sugar cane fields. Any leftover slaves could be peddled for profit in the American colonies. Proceeds from the sales paid for rum, spices, pillaged Mayan gold and gems to sell upon completing the third leg of the triangle with the return to England.

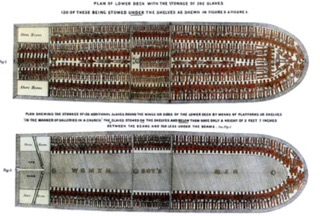

Human cargo stowage plan for a typical slave ship. Wikipedia

Whydah was well-suited for its job. The sturdy square-rigged, three-masted galley was 110 feet long with a hold capable of hauling 300 metric tons or about 330 U.S. tons. Topside cabins could accommodate the captain, officers and even some paying passengers. On a good wind, it could reach 13 knots or about 15 miles per hour. For protection at sea, it had 18 six-pound cannons, which could be upgraded to 28 should they be needed in times of war.

Captain Lawrence Prince was at the helm as the Whydah left its London home port for its maiden voyage early in 1716, sailing down the European coast then past what is now Gambia, Senegal and Nigeria to Benin. Merchandise sold along the way bought some 500 slaves at Ouidah along with gold, Akan jewelry and ivory. From there, Captain Prince pointed the bow toward the Caribbean. Captives who didn’t survive stifling cramped conditions in the hold had a “burial at sea” by being tossed overboard. Inventory shrinkage was a cost of doing business in the slave trade. Surviving souls were exchanged in the Americas for precious metals, sugar, indigo, rum, logwood, pimento, ginger and medicinal supplies. As he began the return leg of the triangle, Captain Prince encountered one of the world’s most successful pirates, Samuel “Black Sam” Bellamy, whose total plunder in today’s dollars would easily place him on the Forbes list of millionaires.

The Pirate

Samuel “BlackSam” Bellamy was quite a dashing figure. All that matters.com

Samuel “Black Sam” Bellamy was a dashing figure – tall, bulked and bronzed from years under the sun in the physically demanding work aboard sailing ships. He accessorized his silk coats and stockings, and silver-buckled shoes with a sash of pistols, handy bling for a man in the piracy business. A silk bow tied his dense mane into a ponytail. He kept his coif in its natural jet black color, instead of dusting it with white powder as was the male sartorial style of the day, thus earning his “Black Sam” moniker.

Sam didn’t start out to be a pirate. He was born in Hittisleigh, Devon, England, on February 23, 1689, the youngest of six children of Stephen and Elizabeth Bellamy. His mother died shortly after his birth. He was fascinated with the sea early in life, joining the Royal Navy as a teen and even fighting a few battles. Military discipline was not his cup of tea, so in 1715 he set out to see the new British colonies, ostensibly to visit relatives on Cape Cod.

Seeing family was only a start on Bellamy’s New World adventure. A local beauty, Mariah “Goody” Hallett, caught his eye and his heart. Her family took a liking to the young suitor, but didn’t think the poor sailor was good marriage material for their saucy daughter. Sam set out to change their view of his financial prospects upon learning of the Spanish Treasure Fleet laden with gold that succumbed to a hurricane off Cuba in 1715. While he headed south, Mariah gave birth to their son, a love child who died as she kept it hidden in a hayloft. She was blamed for his death and thrown in the Old Jail at Barnstable, Massachusetts. Although Mariah was acquitted of murder, she was banished from the colony for her negligence. The jailing must have been jarring for docents swear her spirit is one of the specters haunting the nation’s first wooden jailhouse to this day.

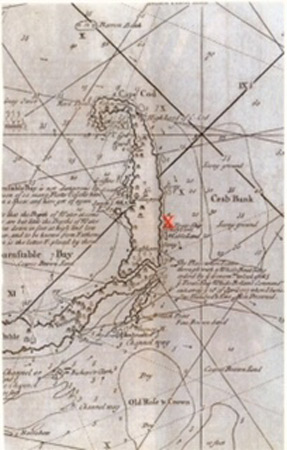

X marks the spot of the Whydah wreck off Cape Cod on Cyprian Southbeck’s map. Thevintagenews.com

Sam had no luck finding the Spanish fleet with its pillaged Mayan gold. However, he fell in with fellow treasure hunters, a British privateer Benjamin Hornigold, who commanded the ship, Marie Anne, and his first mate Edward Teach, later known as “Blackbeard” the pirate. By the summer of 1716, the Marie Anne crew tired of Hornigold’s refusal to attack ships of British origin and mutinied. By popular vote, Bellamy was elected captain, then Hornigold and Teach were expelled from the ship. The remaining 90 crew hoisted a pirate flag then captured a second ship, the Sultana.

Democratic principles were the rule aboard pirate ships. Their diverse crews were men of all national and social origins; liberated slaves, escaped prisoners, indigenous people from islands and nations they visited, and some of lofty social status who hungered for adventure. Popular vote ruled all decisions, and spoils were split equitably among all crew. Black Sam developed a special reputation for fairness. The Prince of Pirates was also called the Robin Hood of the Seas, and his crews were his Merry Men.

Under Bellamy, the two ships could work in concert to overtake and raid other ships. In February of 1717, the pirates set their sights on the Whydah Gally as it sailed through the Windward Passage between Hispaniola and Cuba. Captain Prince quickly realized he didn’t have a chance, and surrendered his ship after the firing of a single shot across its bow. He was rewarded by being given the Sultana in exchange for the Whydah, which became Bellamy’s flag ship. The crew quickly upgraded it to its full 28-cannon complement, and removed the captain’s quarters to make it less top-heavy. The Whydah and the Marie Anne pointed their bows toward the Carolinas with a goal of reaching New England, where Black Sam could show he was no longer merely a poor sailor seeking Goody’s hand in marriage.

Whydah silver displayed at Houston Museum of Natural History. Theodore Scott / Flickr

Pillaging their way north, the crews overtook a sloop under the command of a Captain Beer. Bellamy wanted to leave the ship to its captain, but was outvoted by his crew. So Beer was pressed into service as the growing flotilla of pirate ships sailed northward. In all, some 55 ships were raided by the pirates, who gave crews the option of joining the Merry Men or leaving, oft aboard their mostly unharmed but emptied vessels.

Bellamy’s string of successes ended as he approached Cape Cod, intent on reuniting with his beloved Goody Hallett. Some tales hold he was lured too close to land by the disgruntled Captain Beer and others say it was solely a catastrophe wrought by chance of a powerful hundred-year nor’easter. Regardless, the Whydah was dashed on a sandbar approaching the Cape off what is now Wellfleet, Massachusetts, at 15 minutes after midnight on April 26, 1717. Masts snapped and the heavily-laden ship broke apart in minutes. Only two survived as 102 bodies washed ashore, leaving 42 crew unaccounted for, including Black Sam Bellamy. Survivors were Thomas Davis, a Welch carpenter, and John Julian, a 16-year-old Miskito Indian, who later was sold as a slave to the great-grandfather of U.S. President John Quincy Adams. The Marie Anne wrecked nearby, with seven survivors. Most were hanged for piracy, though carpenter Davis, who had been pressed into piracy against his will, was acquitted.

The Wreck Site

Ship’s bell is on display at the Whydah Pirate Museum, Yarmouth, Massachusetts. Wikipedia

Hundreds of Cape Cod’s infamous salvaging “moon-cussers” quickly descended on Wellfleet’s Marconi Beach to scavenge what could be found of the Whydah’s treasure. By the time Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute dispatched a local salvor named Cyprian Southback to recover its treasure and goods, most of the heavy cargo of gold, silver and cannons had sunk into the shifting sands of a debris field that stretched four miles along the shore. Southback also had been tasked with burying the bodies, but arrived too late for that as well. The job already had been done by the local coroner, who presented him with a bill for his services.

Except for a few items gleaned by local history buffs, the wreck’s treasures were mostly forgotten until 1984, when marine archaeologist Barry Clifford used Southback’s 1717 map to start probing the sands of the shallow wreck site. Since then, annual excavations have yielded more than 200,000 items. Many can be seen at the Whydah Pirate Museum, Yarmouth, Massachusetts. Artifacts include the ship’s bell inscribed with “THE WHYDAH GALLY 1716” plus countless guns, pieces of silver and even a small black leather shoe believed to have belonged to a 10-year-old boy who insisted upon joining the pirate crew against the wishes of his mother, who had been a passenger on what became the world’s most successful pirate ship.

Author: Bob Sterner

Bob Sterner has covered sport diving and marine conservation with stories and photos as a staffer and freelancer for leading magazines and news organizations. The founding co-publisher and editor of Immersed, the international scuba diving magazine, he has represented the publication and been a presenter at scuba diving trade shows across the US, Canada and Asia.

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

All Rights Reserved © | National Underwater and Marine Agency

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Web Design by Floyd Dog Design

Another fascinating tale!

This would make a great movie.

Yes it’d make a great movie. Maybe Dirk should branch out into cinema.

We know Dirk can do it! Have collected Clive Cussler books for a few years and I am very impressed with him carrying on his father’s legacy. Keep up the good work, Dirk Cussler!